Photo by Callum Shaw on Unsplash

Persistent Problems Need More Effective Solutions.

Welcome to Part Deux of our Solutions Of The Year Slideshow. (If you haven't seen Part One yet, you're missing out.) Last week we curated a list of solutions that simplified the onerous — ideas that eliminated barriers to getting people the support they need.

This week, ripped from the pages of our Solutions of the Year Magazine, we bring you stories of innovative responses to what can appear to be entrenched problems. The climate crisis, affordable housing shortages, structural racism, the nonprofit industrial complex ... no easy fixes. But scroll through and get inspired by the people, programs and groups who are finding new approaches to inequities in housing, philanthropy, child welfare, clean energy and other sectors.

Change is happening. And we are here for it.

Housing protest in Philadelphia in September 2020 (Photo by Michael Stokes/CC BY 2.0)

Next City's housing correspondents Jared Brey and Roshan Abraham have written several stories about Philadelphia's Eviction Diversion Program, which boasts a 93% success rate to date. (Watch our Solutions of the Year Anti-Racist Pecha Kucha webinar to hear Rachel Garland from Community Legal Services (CLS) present on the benefits of landlord-tenant mediation.) Next City's hometown ended the year in housing on a high note. In November the City Council voted unanimously to enact a renter’s right to counsel, the fifth major U.S. city to legally mandate that all low-income renters would be guaranteed a lawyer to fight their evictions. (CLS says about 90% of tenants in the city go through the eviction process without legal assistance.) And on December 16, the council voted to make the Eviction Diversion Program permanent (though how it will be funded remains a question mark).

A meeting of Corona Plaza vendors. (Photo courtesy Street Vendor Project)

Gig workers often operate at the whim of large corporations or government entities. But in 2021 we saw ride-hail drivers, food delivery workers and others organize (formally and informally) to carve out more equitable employment or ownership models and keep money in their local economies. Oscar Perry Abello reports on the Street Vendor Project, which worked with licensed and unlicensed vendors, specifically in Queens' Corona Plaza, to fight for the kind of change that benefits everyone. What can we learn from their organizing work? For a deeper dive, check out Abello's Bottom Line Solutions of the Year Webinar with Street Vendor Project Director Mohammed Attia and Deputy Director Carina Kaufman-Gutierrez.

Illustration by Dylan B. Caleho

Among the many stellar stories that Steve Volk wrote for Next City this year was a two-part feature about how Black and Brown children are removed from their families at disproportionately high rates, for reasons owing more to economic hardship (poor housing quality, food insecurity) than endangerment. You won't forget the story of Kyeesha Lamb, stuck in the "system" with two children taken from her despite no evidence of wrongdoing.

But Volk raised up a program in Nassau County, Long Island that showed great promise. With "blind removal meetings," when social workers presented case files to colleagues and superiors to determine whether a child should be placed in foster care, all identifying information was redacted -- name, address, neighborhood, and so on. This effectively removed the prospect of implicit bias in decision-making, and the number of removals went down nearly 60% in the first year alone.

jackie sumell, originator of the solitary gardens project (Photo by Maiwenn Raoult)

Nine garden beds lay next to one another in New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward, each six feet by nine feet, each the size of one standard solitary confinement cell. The gardens are a mix of plants with medicinal and aesthetic properties; growth is limited to the parts of the tiny space where a person would be free to move in a solitary cell; space is blocked off where the bed and toilet would be. The plants in each garden are chosen by someone in solitary confinement and planted by a volunteer gardener on the outside. The solitary beds eventually overrun with plant life, a visual representation of a world without prisons, an idea which forms the project’s core mission.

“What the garden has done is give me a greater appreciation of all the things that I am no longer able to feel, touch or enjoy," says Tim Young, who is incarcerated at San Quentin State Prison. "I haven't touched the earth or leaned upon a tree in over 22 years.”

Image by Mark Hultgren/Pixabay

Foundations represent more than $1 trillion in invested assets, yet are required to give away only 5% of their assets to charity every year. What are they doing with the other 95%? That's the central question of Oscar Perry Abello's penetrating feature story on how foundations such as Heron and Nathan Cummings are intentionally investing in companies or projects that generate positive social impact, and that align with their grantmaking missions.

"Critics have pointed out the harmful and sometimes hypocritical features of the traditional foundation model. A foundation that grants money to groups pushing for criminal justice reform might also invest in private prisons," Abello writes. Some go even further to say that everything about the current foundation model, "from the process of selecting grantees to their investment strategies ... perpetuates the white supremacist power structures that created them in the first place."

Photo by Third Dune Productions/Image courtesy Matt Barton and Black Cube

Photo courtesy of Lexi Tsien

Reporter Phil Roberts digs into Dark Matter University (DMU), a democratic network of about 140 design academics and professionals — mostly Black, Indigenous, and other people of color — with a mission to “create new forms of knowledge and knowledge production through radical anti-racist forms of communal knowledge and spatial practice that are grounded in lived experience.” By using their positions inside established programs, members hope to challenge, educate and redefine design education so that more socially conscious graduates become the professionals of tomorrow. (For more, see DMU Core Member María A. Villalobos in her presentation at our Solutions of the Year Anti-Racist Pecha Kucha webinar.)

Proposed net-zero emissions housing project by Jamaica Plain Neighborhood Development Corporation (Rendering courtesy JPNDC)

Across the United States, affordable housing policies are becoming increasingly responsive to on-the-ground realities in cities. Building homes for low-income residents is just the starting point. Connecting affordable units directly to goals for anti-displacement, climate change and internet access goes beyond simply providing a roof overhead. To hear about examples from Austin, Boston and NYC, check out our Solutions of the Year Housing webinar, moderated by Housing Correspondent Roshan Abraham.

Photo by Lunar Haus

Grassroots inspiration from reporter Tia Graham. When officials in Highland Park, a predominantly Black city surrounded by Detroit, struck a deal to settle a $4 million debt to DTE Energy, the utility removed about 1,200 streetlights. (Not the inspiring part.) In stepped Soulardarity, a community-led organization that advocates for energy democracy. Since around 2012, they've been installing solar-powered street lights that also provide community wi-fi. When DTE proposed a $4.2 billion electric infrastructure plan for the region in 2018, Soulardarity called for the Michigan Public Service Commission to reject it because the plan didn’t include community solar.

Battery storage system at D.C.‘s Maycroft Apartment complex. (Photo courtesy Jubilee Housing)

Apartment renters often miss the opportunity to convert their individual units to clean-energy power. Reporter Ambika Chawla brings us the story of the Maycroft, a low-income apartment building in D.C.'s Columbia Heights neighborhood that's taking the community solar approach to power-sharing. Community solar allows households that can't afford on-site solar to receive a portion of their electricity from a remote solar project. Maycroft also launched a one-of-its-kind Resiliency Center, which provides residents with a powered community space, which can last for three days in the event of a city-wide power outage.

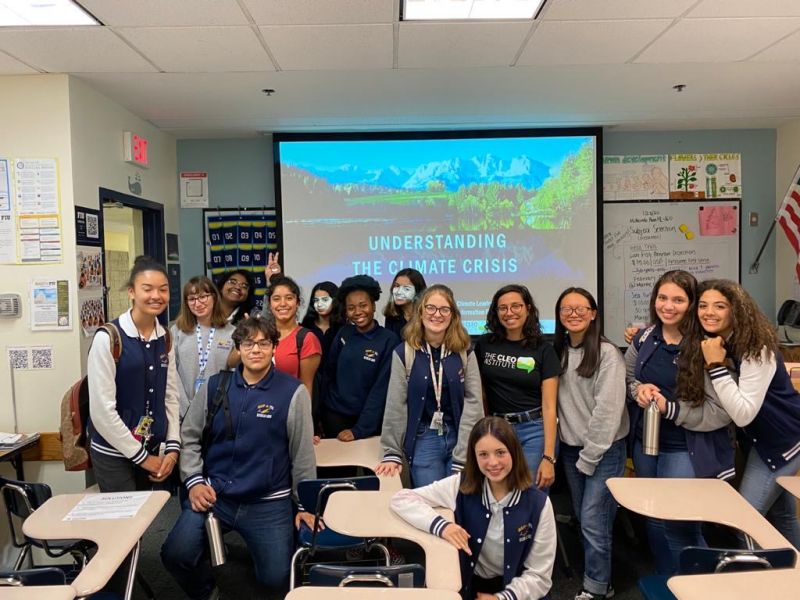

FIU High School students pose after Climate Speakers Network training (Photo by Enith Hernandez, courtesy CLEO)

Next City contributor Cinnamon Janzer profiles a program that trains Miami high-schoolers how to be effective communicators about the climate threat facing their generation. The CLEO Institute, a non-profit dedicated to cultivating an informed public that supports climate action, started in 2019 its Climate Leadership Information Program (CLIP) — an after-school program that trains students as climate speakers. After training, students give presentations on climate to their classmates and families and participate in public service and social media campaigns that highlight specific climate issues they care about.

We are in the final week of our year-end fundraising drive. If you want Next City to continue our reporting, we must achieve our end-of-year fundraising goal. We’re reader-supported. But we don’t yet have enough monthly donors to sustain our work.

Will you donate today? Anyone who contributes before the end of this year will have their donation matched! And you will receive a free copy of our Solutions of the Year magazine.

Thank you for your support. Wishing you peace, good health and justice for 2022.

P.S. Remember to catch Part 1 of our Solutions of the Year slideshow as well.