This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberThe frustration was palpable in the crowded Philadelphia auditorium. It was the last in a winter-long series of hearings and meetings about the future of the city’s troubled schools. By the end of the public meeting, it would be decided which fatally underfunded city schools would close before the following fall. Upwards of 30 people were signed up to testify before the body appointed to make the decisions, the unelected School Reform Commission. Almost all the speakers were there in a last-ditch effort to save their neighborhood school.

During a lull after the second public speaker stepped down, a voice burst from the crowd: “You know damn well what we all have to say, and you are a coward if you don’t listen to us! Only a coward could vote to close schools!”

After 120 minutes of impassioned testimony, and many more angry outbursts from the crowd, the SRC would vote to shutter 23 of 27 schools on the list, the largest number of school closings in Philadelphia’s history. Upon the commissioners’ vote to close 100-year-old Germantown High, a woman wailed with rage: “The whole city needs to be shut down, shut this city down!” But it was an empty threat. The protestors had already closed off north Broad Street outside the school district headquarters, and 19 activists had been arrested for blocking the entrance to the building. The Civil Affairs police looked on placidly.

Welcome to the world of public engagement 2014, a rite of bureaucratized democracy that is probably in equal parts valued and despised by everyone involved in its legally mandated production.

Public engagement — when a decision-making body asks the general populace for formalized input, outside of a voting booth — is a relatively young term first used by The New York Times in 1998 to describe the political lethargy surrounding the presidency of Bill Clinton. If you scroll through the Times’ archive, you can’t miss the concept’s ascendency into the cultural mainstream. The phrase appears with increasing frequency from 2002 on, in articles about electoral politics, trends in museum operations, art, university controversies and philanthropy. In 2009, President Barack Obama changed the White House’s Office of Public Liaison and Intergovernmental Affairs to the Office of Public Engagement.

The rise of engagement as a popular currency can be interpreted in many ways. It has something to do with the rise of the Internet, something to do with our increasingly public ways of interacting with one another, something to do with why Obama was elected and could create an Office of Public Engagement in the first place. But perhaps nowhere is the trend so pervasive as in cities, where local government agencies have for decades been mandated to hold open hearings before making decisions on land use, education, utilities, public housing and various other matters involving taxpayer dollars.

The proliferation of formal processes dedicated to gathering public opinion can be traced back to the civil rights era. Sit-ins and protests, made famous in the battle over Jim Crow in the South, were used in northern cities as well, where welfare offices and public housing developments were ground zero for fights over racist housing, welfare and employment practices. In these official settings, authorities tried to defuse unrest by granting some semblance of democratic process. Better a hearing, the reasoning went, than the three days of rioting that broke out in Boston in 1968 after police tried to forcibly remove militant activists from a Roxbury Crossing welfare office. Similar rioting swept through cities across the nation, terrifying authorities into making concessions they considered necessary to quell the unrest: welfare spending and urban aid skyrocketed.

“The welfare crisis led to the proliferation of hearings, forums, conferences, and meetings devoted to the subject of relief giving,” write Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward in their 1978 classic, “Poor People’s Movements.” Piven recalls that in the early 1960s, many of the hearings were “perfunctory and dismissive of ordinary people.” But “as the movements became stronger, more raucous, more disruptive, the public officials became more conciliatory,” she writes.

Over the past several decades, an entire cottage industry has sprung up around community engagement. Consultants specialize in it. Public agencies and local governments collectively spend millions carrying our hearings in service of it. Now techies are vying for a seat at the table, advocating limitless possibilities for reimagining engagement on the Internet. Start-ups like venture-capital-backed MindMixer and Berkeley-based Peak Democracy create websites designed to make it as easy as possible for people to weigh in online.

“Being online allows these organizations to reach a broader [audience] who are not able to show up [for a meeting] and the best way to exert influence … is to show that there are a lot of people who care about a particular issue,” said Nick Bowden, CEO of MindMixer. Among his clients are the City of San Francisco, Chicago’s parks agency, Kansas City’s government and the Washington, D.C. public school district, which brought on the company to generate input on its school closure plan in 2012 and has continued to contract MindMixer to build dialogue on district budgets and other matters.

MindMixer does not release information on its profitability, but observers believe the start-up has the potential to earn plenty of revenue from its client base of public agencies and others soliciting public input. In 2013, the company raised $4 million from investors.

Ron Whitehorne is a former public school teacher in Philadelphia who has been fighting for better public schools since the 1960s. He said public dialogue has become more sophisticated since the civil rights era — thanks to the addition of public relations professionals, consultants and products like MindMixer — but not necessarily any more productive.

“It’s all about how to manage dissent,” said Whitehorne.

His opinion is shared, to varying degrees, by those on all sides. After one particularly controversial round of school closures in New York, Mayor Bill de Blasio, then the city’s public advocate, issued a report on the public engagement process in 2010 that concluded with recommendations for significant reform. The Department of Education, he wrote, “treated these hearings as procedural hurdles in order to satisfy the letter of the law, rather than an opportunity to engage in a productive dialogue … .”

Political scientists who study democracy say that the processes typically lack the clear goals and metrics for assessment that help generate impact. “Many participation practices in cities and elsewhere at all levels of governments, in my view, are not very constructive,” said political scientist Archon Fung, author of “Empowered Participation: Reinventing Urban Democracy.”

“The public hearing process, they all look the same all over the world. In most cases people don’t learn much except that public officials might find opposition to their policy is greater than they had thought and that kind of thing doesn’t prove very useful because officials don’t intend to change their mind as a result of that exercise.”

Luz Mayi, a community member in Jersey City, N.J., talks during a rally against the use of taxpayer-funded vouchers for religious and private schools. (AP Photo/Julio Cortez)

Take the public hearings over the highly freighted issue of mass public school closings in poor urban school districts. Philadelphians weren’t the only ones holding public meetings in recent years. Similar public processes took place in Detroit, Chicago, New York and Washington, D.C.. But in all cases, no matter the volume of public engagement or degree of opposition aired, the plan approved at the end of the process was not hugely different from the original plan, and public response was no less negative. Even for public servants and committed activists, it’s difficult not to wonder, does the input matter?

Even protestors who see favorable outcomes walk away frustrated.

Andrew Saltz came to the Philadelphia hearings to fight for his job, and for the welfare of students he believed deserved better. An award-winning 31-year-old teacher, education blogger and self-described gym rat, Saltz organized students to attend public hearings on the proposed closure of their school. Though he ultimately saw his school saved from closure, the process frustrated him. “I think these meetings were to say they had those meetings. Civic engagement, check that off, we’re done,” Saltz said. “It was just basically people screaming into the ether and [the officials] at the meeting nodding politely.”

“It was just basically people screaming into the ether.”

It’s a broken link that Stephen Danley says must be fixed if cities want to see social and political change.

Danley, an assistant professor of public policy and administration at Rutgers University-Camden (and occasional contributor to Next City), spent several years studying grassroots community organizations and what he describes as “micro-local urban policy networks” in post-Katrina New Orleans.. He argues that groups with limited means to affect change in a particular arena take the tools they have — public processes, social media, the courts, political access, — and use them to maneuver in the arena they’ve been locked out of.

“When [the public is] involved in [a] process, they are cooperative with city officials and help input local knowledge into the political system,” he wrote recently in a paper about democracy in marginalized urban communities. “When they are ignored and excluded, they use creative and coercive means to have their voices heard.”

One example of this comes from New Orleans, where service on a ferry connecting a working-class neighborhood to the city’s downtown had been cut. The public agency controlling the ferry defended the cuts as a necessary cost-saving measure and refused to restore services even after a massive outpouring of opposition at numerous formal public hearings. After being shut down again and again in the formal process, a community group called Friends of the Ferry filed a public records request and discovered that toll revenue promised for the ferry had been diverted to support a nearby highway instead. Friends of the Ferry passed their findings to a state senator who then used the new information as as a political lever to pressure the agency to reinstate the services. It worked.

“If people are angry they didn’t get a voice, they will find their voices in some other way,” Danley said. “They will find their lever to change the system and they will be creative about how to find it.”

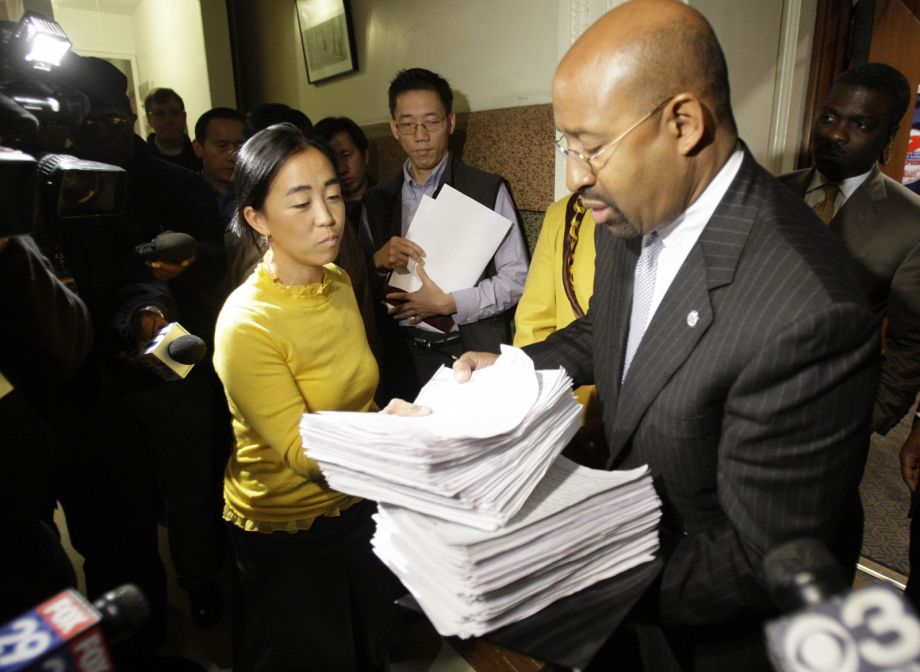

Helen Gym has become something of an expert at finding Danley’s elusive lever.

Philadelphia activist Helen Gym presenting Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter with signed petitions. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

“Civic engagement is about developing relationships and deeply understanding each school and school community’s needs and priorities,” said Gym. “But institutions that are reluctant to change are not going to engage well. As much as we might like to think people want to do the right thing, they have to be compelled to do the right thing especially when they are faced by multiple forces pulling and pushing.”

One of the Philadelphia commissioners who voted to keep Saltz’s school open was Joseph Dworetzky. A lawyer by profession who spent four years as a School Reform Commissioner before his term ended in January, he was often the only commissioner voting against the district on proposed closures. While he left the SRC in frustration, he believes that formal community input has a role in public decision-making, even if isn’t as immediately evident as activists would like.

“In each case, community input was either the key factor or one of the key factors in those decisions,” he said. “If no one turns out and no one seems to be really upset, it’s not hard to conclude that no one really cares. It’s definitely a factor you notice even if it’s not the only factor.”

A growing body of research indicates that this sort of local activism, formal or informal, may be the most effective way for non-wealthy Americans to actualize their political will. The authors of the 2012 book “The Unheavenly Chorus: Unequal Political Voice and the Broken Promise of American Democracy” found that the poorest Americans are less likely to be politically involved in any category, national or local, but when they do get involved, they are more likely to engage on a local level and outside the voting booth. In other words, lower-income Americans are more likely to attend a public meeting about the future of their neighborhood school than vote for the next president. “It is possible that the disadvantaged achieve greater voice — for example, through community groups — in local politics than national politics,” authors Kay Lehman Schlozman, Sidney Verba and Henry E. Brady write. Other research has shown that discrepancies in local participation rates between people of different income levels dissipate when people perceive their participation will have direct implications for their community.

“If people are angry they didn’t get a voice, they will find their voices in some other way.”

“The general pattern is that people who are better off participate more, whether it’s voting, contributing to campaigns, or going to meetings, than people who are less wealthy or less well educated,” said Fung, a professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. “But if you look at forms of participation that focus on the needs of the less well off you find that they participate more than better-off people.”

An example of this can be found in Porto Alegre, Brazil and a growing number of cities around the world, including Chicago and New York, where participatory budgeting allows the public to vote on how some tax dollars are spent. There, lower-income residents dominate the proceedings, Fung said. (These empowered assemblies are a result, notably, of increased pressure from populist movements and substantial unrest.) The usual result is heightened spending on services for low-income residents, demonstrably resulting in lower rates of infant mortality and greater investment in education.

Courtney Thornton, 10, looks at her candle during a candlelight vigil outside the Chester-Upland School District administration building in Chester, Pa. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum)

“If participation gives poor people a real opportunity to affect what is important in their lives, they will participate,” Fung said.

Today, online tools like MindMixer have the potential to vastly reshape the landscape of participation. Anyone with access to an Internet connection can use these tools to, in minutes, register an opinion or vote. Ideally, the system works something like it did for a D.C. user named Rebecca S. In the midst of the public process about school closures in the District, Rebecca wrote a short blog post on the platform — called an “idea” — arguing that her neighborhood public school, Francis Stevens Elementary, should be removed from the list of proposed closures. The Ward 2 resident, then pregnant with her second child, explained that her three-year-old goes to school at the endangered public school and that the entire family, including the dog, enjoyed playing in its playground and admiring its community gardens. She wanted the option of sending her second child there too. Five people commented on her post and 34 viewed it, according to the site’s page analytics. After more on- and offline lobbying by residents of the fast-gentrifying section of Northwest D.C., Francis Stevens was one of five schools kept open as a result of the public process. With a minimum of physical effort and zero schlepping, a very pregnant Rebecca S. had helped guide the district’s decision-making.

In total, 300 parents, teachers and community members used MindMixer throughout the D.C. school closing debate, sharing 200 ideas on how to refine the district’s plans, some of which attracted as many as 40 comments, according to MindMixer. But while it’s inarguable that the online platform holds the power to bring the conversation to those who have a hard time physically accessing public meetings, most research indicates that the social class dynamics of political participation are no different online than they are in person: those with higher incomes are still overrepresented.“A lot of organizations like MindMixer are doing really great work to make it easier for people who want to participate,” said Hahrie Han, associate professor of political science at Wellesley College.

“But first you have to motivate and develop capacity [among those who aren’t already engaged]. The challenge is for organizations like MindMixer to work with organizations that are doing capacity building. The marriage of those things could really democratize the public-comment process.”

But the democratization of public engagement is already happening online and informally. In April, the New York Police Department asked its Twitter followers to share photos of officers in their communities using the hashtag #myNYPD — and people did. Hundreds of photos were shared thousands of times. Unfortunately for the department, the photos that went viral weren’t exactly flattering. Among the top #myNYPD tweets were images of officers wielding batons at Occupy Wall Street protestors, sleeping on the job, restraining surprised-looking civilians and searching men of color. It was a case of the “reality of perception” breaking though, Zeynep Tufekci, of the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University, told NPR following the episode.

Indeed, the NYPD got a reality check. But instead of burying the photos, the department now has a chance to take what it learned and use it for growth in the same way an agency ideally uses any other feedback it gathers.

It’s an opportunity, Tufekci said, “if the people running the institution look at it and say, ‘Whoa, what just happened? Let’s think about this.’”

In Philadelphia this winter, the school district started another public engagement process. The issue is a proposed universal enrollment program that would allow all children to apply for enrollment at district schools — including selective-admission public, charter and potentially Catholic schools — using a common application. The child would then be assigned to, in theory, the best receiving school based on an algorithm created by whichever private company is brought on to run the program.

Hundreds of attendees crowded a meeting in January. After the school district’s presentation and discussion, the spokesperson for every single table declared they were opposed to the universal enrollment program. The arguments against were legion, but Lisa Haver, a longtime education activist and former district teacher, summed up the opposition succinctly. “Our concern is that we seem to be asked about something that is presented as fait accompli,” she said at the end of the meeting. “The indication is that there are going to be more meetings and our feeling, and it seems like everyone else’s, is why are we doing this? I would love it if we could just take a vote right now and put it to bed. … We’re here, take a vote.”

The school district demurred, and the meetings continue to be scheduled. Haver and her allies plan to be there as the conversation escalates. “You have to mobilize, you have to agitate, you have to protest,” said Hiram Rivera, executive director of the Philadelphia Student Union, a coalition of public school student activists. “Every year, we get more young people out there making their voice heard.”

If you ask Danley, that is exactly the right way to make change. “It’s always a small group,” he said, “until it isn’t.”

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Matthew Godfrey is a Philadelphia-based photographer who specializes in commercial, editorial and portrait photography. After years of working as a newspaper photographer, he realized his love for meeting the people he photographs and learning about their accomplishments. Matt studied at Temple University, where he obtained his degree in journalism from the School of Communications and Theater. He currently teaches undergraduate students at Temple. Aside from his personal photography work, he also spends time photographing for the event photography company he co-founded, Fairmount Photography, which specializes in events and weddings.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine