Kritsada Rotcharatch shows a photo of his inundated neighborhood in Sai Noi.

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberThis special issue of Forefront is part of The Rockefeller Foundation’s Informal City Dialogues, a year-long collaboration with Next City and Forum for the Future taking place in six rapidly urbanizing cities around the world. The project aims to foster a conversation about creating more inclusive and resilient cities. Read weekly dispatches from our cities, watch short films and engage with others at nextcity.org/informalcity .

When the water started rising in October 2011, the ground snapped and squeaked as it broke into pieces. Bricks shattered, floor tiles cracked and water rushed up through the fissures. The deluge blindsided the 150 families living here, in a cluster of villages known as Kittiyarak nestled in Thailand’s Sai Noi district in Bangkok’s northwest suburbs. By the time the devastating flood receded some three months later, it would be on record as the worst natural disaster in modern Thai history.

“No one expected it to be this bad,” says Fongpol Konpruek, a 52-year-old former farmer from northern Thailand who moved to Sai Noi 16 years ago. “We were the first ones wet and the last ones dry.” Konpruek remembers the overwhelming confusion of those early days. “The water came from everywhere. It came slow, but it also came fast. I don’t know any other way to explain it.” Rising 20 to 30 centimeters per day until reaching a height of 1.5 meters, the debris-clogged tide submerged streets, sidewalks, parking lots and the ground floor of every building in the area.

What happened next says a lot about the power of social networks and informal systems in moments of urban crisis. Left with little official help, residents here — along with hundreds of thousands of people in other flood-struck parts of Bangkok — sprang into action. They quickly improvised a series of informal networks, and repurposed existing ones, to perform the vital tasks normally carried out by the government in emergencies. People with no training and few resources built barriers and monitored flood levels, delivered food and drinking water, evacuated residents trapped in their homes, provided medical services to the sick and injured, and policed their neighborhoods for looters. And when the water receded, these networks shifted focus and led a localized cleanup and rebuilding effort that helped the city rebound.

A child waits in the shade while workers harvest nearby in Sai Noi. These fields were inundated during the flood in 2011.

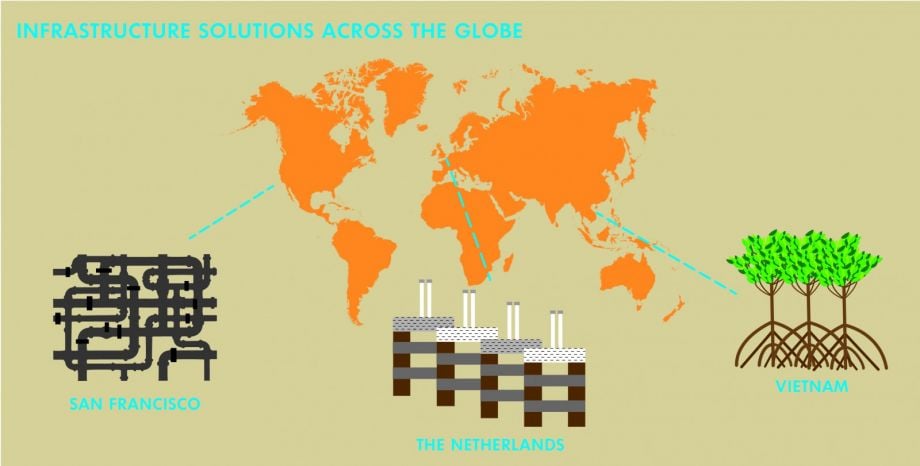

As cities around the world grapple with rising sea levels and strengthening storms, governments are responding with an array of infrastructural solutions. Since Hurricane Sandy, New York has increased the minimum elevation required for new and reconstructed buildings in flood-prone areas, and is raising subway entrances and ventilation grates off the ground. San Francisco is redesigning its water and sewage treatment system to the tune of $40 million to prevent rising sea waters from entering the pipes during storm surges. The Netherlands — nearly 60 percent of which is prone to flooding — is reimagining its entire coastal protection system, one of the most elaborate in the world, by allocating at least a billion euros annually to extend storm-surge barriers, relocate tidal channels, nourish beaches and increase the flood-protection levels of diked areas “by a factor of 10.” And for every mega-project like these, there are smaller, micro-targeted ones: The modest but growing Vietnamese city of Quy Nhon, for example, is spending $550,000 to restore 150 hectares of mangrove forests, helping to protect 14,000 households along its coast from strengthening monsoons.

But there’s also a growing awareness that combating disasters with hard infrastructure alone ignores half the equation. Perhaps just as important is a city’s social infrastructure. Recent research suggests that informal networks are critical to dealing with calamity and that areas with strong social cohesion fare better than areas where such networks are weak.

Bangkok isn’t the only place recognizing this. San Francisco’s Empowered Communities Program is working with local neighborhoods to increase their resilience in advance of disasters. The initiative supports communities as they develop action plans, but also generates higher levels of social capital among key stakeholders that can be invaluable during traumatic events. Participating groups include Neighborhood Emergency Response Teams (NERTs) and merchant associations. The city has even created a role-playing game called Resilientville that helps communities test and streamline their informal emergency response capabilities.

One of the most comprehensive efforts currently underway is in Wellington, New Zealand, where the largest unit of that city’s emergency management office is the Community Resilience Team (CRT). Dedicated solely to equipping and empowering informal networks to respond when disaster strikes, the CRT trains “Community-Driven Emergency Management” (CDEM) volunteers in how to promote preparedness among their own networks, as well as to respond as a community or plug into the official government response. Community response plans are facilitated by the CRT to guide planning at the local level to coordinate activities and manage resources like food and fuel. “Our whole model is getting normal people involved,” says Dan Neely, senior adviser for emergency preparedness at the Wellington Emergency Management Office. “People who are capable in their daily lives will be capable during an event. We’re trying to get to those people now… so that when a large-scale event happens, John Doe can tap into the wider community response plan.”

Wellington sent some of their CDEM volunteers to Christchurch when that city was devastated by an earthquake in 2011. But Neely emphasizes that you can’t just parachute in an informal response. “Part of this is building social capital,” he says. “We’re working to increase connectedness. Strong communities have better outcomes during a response.”

For evidence of this, look to Chicago, where informal networks played a major role in determining survival rates when a five-day heat wave killed 733 people in 1995. As Eric Klinenberg recently reported in The New Yorker, the neighborhoods that lost the fewest lives during that event weren’t necessarily the richest, but rather the ones that had especially strong social ties. His book Heat Wave documents the surprisingly high survival rate in the working-class Latino neighborhood of Little Village: “The social environment of Little Village protected not only the area’s Latino population, but the culturally or linguistically isolated white elderly, who were at high risk of death as well.” He points to the neighborhood’s “social contact, collective life and public engagement” as factors that “foster tight social networks among families and neighbors.” When crisis struck, those networks responded almost instinctually.

Such informal networks were critical lifelines for many in Bangkok in 2011, and as storms intensify and sea levels rise, they’ll only become that much more crucial. Cities everywhere are grasping the importance of such networks, but in many ways Bangkok has a head start — it’s a place where informality already infuses many aspects of everyday life. “The government is inefficient and corrupt,” says Bangkok-based engineering professor Visit Hirankitti, who is working on methods to enhance the city’s informal disaster response. But what Bangkok lacks in bureaucratic competence it makes up for in people-powered strength.

Ideally, a combination of capable government and robust informal networks, working in tandem, could provide the bulwark that cities will need in the age of climate change. This will require not only social cohesion, but a willingness on the part of governments to help equip communities for self-reliance and develop disaster plans that allow for a citizen-led response. There are signs that this is slowly occurring — from New York to Bangkok, recent events have forced cities to let informal networks react to disasters with relative autonomy. Whether they embrace a model in which private citizens and government agencies work in partnership could define their resilience as the coming storms arrive.

In Bangkok, informal networks are not only strong, they’re omnipresent. They have their roots in rural society and are intricately interwoven with the social fabric, even in urban areas. The greater metropolitan area has grown rapidly in the last several decades, doubling in size since 1980. In search of economic opportunities, migrants from the countryside have driven much of that growth. Despite the speed of this population expansion — or perhaps because of it — its residents have maintained strong social bonds. Such robust informal networks are also the product of a population that expects little of its government, aside from two revered institutions, the monarchy and the military.

Those networks attained new importance in late 2011, after Tropical Storm Nock-ten had made its way overland from Vietnam to Thailand in July. Over a period of weeks, rain from the storm, combined with heavy seasonal monsoons, overwhelmed the city’s dams. The Grand Palace was deluged, and Don Mueang Airport shut down after water flooded its runways. Panic gripped the city as the government declared a five-day emergency holiday. When all was said and done, 815 people were dead, 14 million were affected and over $45 billion in damage was left in the catastrophe’s wake, making it the fourth-most expensive natural disaster ever.

But in the days before the flood arrived, official channels of communication were strangely sanguine. The government urged Bangkok residents to stay calm, insisting there would be no emergency. As late as October 13, the Bangkok Post quoted the city’s governor, MR Sukhumbhand Paribatra, saying: “Right now, everything is under control. If we can’t control it, we will let people know straight away.” And even as the news media reported on the gigantic rain-fed pool growing ominously to the city’s north, they assured Bangkok’s residents that the water would never reach them.

Soon, however, dramatic images of the destruction of Southeast Asia’s second-largest economic powerhouse were swirling around the globe. But hardly anyone was looking at Sai Noi — not the media, and certainly not the government, which proved overwhelmed, unprepared and impotent in the face of a worst-case scenario. By late October 2011, the villages of Sai Noi were isolated and in dire straits.

A little over a year after the flood had receded, I hopped in a taxi one weekday morning and made the 45-minute drive from the gleaming shopping malls and high-rises of Bangkok’s central districts to the district of Sai Noi. I wanted to speak to residents there about how they had dealt with the flood, and how they’ll respond to the next big one, which nearly everyone is expecting someday soon.

Sai Noi is where booming New Bangkok collides with the rural customs and lagging economic growth of Old Thailand. In feel, it is neither urban nor rural. Instead, it’s a mishmash of the two, with rice fields and winding village lanes abutting the strip malls and multi-million-dollar commuter villas of Bangkok’s ever-expanding urban sprawl. It was areas like these, on the city’s north side, that were hit hardest by the flood and where the citizen networks were strongest. In part, they bore the brunt for geographic reasons, but also because the authorities decided to sacrifice them, releasing water into suburban areas in order to staunch the flooding in central Bangkok.

Vichain Kongsub, the elected chief of his village in Sai Noi. He and the local residents’ committee quickly improvised a plan when it became clear the flood would reach their area.

Surprisingly, there is little bitterness about this among the residents; their attitude is more like resigned acceptance. “It’s true that we were sacrificed, but not as badly as other areas,” says Vichain Kongsub, an affable man of 75 whose energy and trim build make him appear 20 years younger. “And anyway, what can you do? We had to suck it up.”

Vichain was at the center of Sai Noi’s informal flood-relief network. As the phu yai baan — which translates roughly as “village chief,” an elected, semi-official advisor found in nearly every community this size in Thailand — the people looked to him for direction. When it became obvious that the floodwaters would reach them, Vichain quickly called a meeting of the local residents’ committee, a nongovernmental body of 15 elders, to create an action plan for the community’s response.

Through consensus, the committee members decided how best to use the two resources the government had provided: Sandbags and a large water pump. “It was all very informal,” says Vichain. They organized residents into work crews — men shoveled sand and women carried the sandbags — and collected money from community members to buy a second water pump. The hope was, at least in these early stages, that they could stop the water from entering the villages. As it surged in, however, their defenses were overwhelmed. “We did our best,” says Vichain, “but it just didn’t work.”

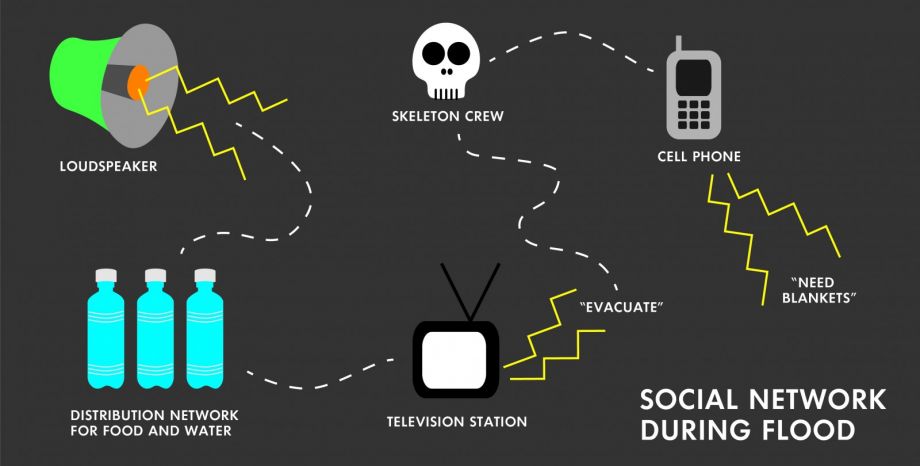

Undeterred by this initial setback, the community found its stride as the situation worsened. Using a loudspeaker mounted on an electricity pole, Vichain and the residents’ committee organized a distribution network for food and water that was flowing into the area courtesy of a city-wide volunteer network formed by the television station Channel 3. Then, with the floodwater rising rapidly, they set into motion an orderly evacuation of residents. They selected six volunteers who would stay behind to monitor the situation and police the area for looters. All the while, this crew of volunteers was in touch with officials at the local sub-district government office by cell phone, to whom they provided updates, as well as the military, which was intermittently delivering aid to Sai Noi.

As one of the leaders of his village’s informal response network, Kritsada Rotcharatch was one of six people who stayed behind during the flood.

Kritsada Rotcharatch, a brash construction foreman who favors t-shirts with the sleeves cut off and carries a cell phone that rings constantly, was one of the six who volunteered to stay behind. He moved to the second floor of his house (the ground floor was underwater) where he kept an eye on property for his evacuated neighbors, who checked in regularly by phone. Kritsada armed himself with a gun for confrontations with looters. “There were no police. My role was to protect the neighborhood,” he says. I asked if he was prepared to use it. “Yes. And I wouldn’t have aimed for the legs,” he chuckles. Kritsada maintained a running list of who was in the community at all times and relayed the information about what he saw to the sub-district office. During this period, he and the five other volunteers were the sole authority governing this area of Sai Noi.

By the end of December, the floodwaters had receded from area. Residents returned and turned their attention to recovery. Cleanup crews made up of five households each collected debris from public areas and worked to put their homes back together. Then, through a system of barter and labor exchange — money was scarce due to the disruption of business caused by the flood — community members tackled larger jobs like repairing their houses. The villages were back up and running in less than a week. In the three months since the water had appeared, not a single member of the community had died or was seriously hurt. Against all odds, law and order had prevailed, and life returned, more or less, to the way it was before. With minimal help from the government, the neighborhood had survived the worst disaster ever to hit Thailand.

Near the end of a long conversation with Vichain and Kritsada, the dark stains of the high-water mark still clearly visible above us on a nearby wall, the discussion shifts to other cities that have been struck by natural disasters in recent years. I bring up Hurricanes Sandy and Katrina, and the hostility that residents of New Orleans and New York felt toward their own governments in the aftermath of those events. I ask them if they felt something similar. “No,” Vichain says without hesitation. “The government already had their hands full managing the water as it moved down from the north. They can’t take care of everyone.”

Cooperation came naturally to the residents of Sai Noi, in this case partly because of another shared identity: Their background as migrants from rural northern Thailand. In these regions, in particular the hardscrabble Isan area in the northeast, flooding is common and the people know how to deal with it. The residents of Sai Noi brought that knowledge with them to Bangkok. “I experienced my first flood when I was four years old,” Vichain says. “People in the countryside are better prepared. We had boats and built our houses on stilts.”

But there was more to it than that. Although they hadn’t come from the same province and didn’t know each other when they arrived, the residents shared a cultural sensibility that, when they found themselves in unfamiliar urban surroundings, brought them together as a community. “It’s very normal for us to cooperate like this. It’s instinct,” says Kritsada, echoing a sentiment I heard from a range of Thais involved in relief networks, including those who’ve spent their entire lives in cities. Sai Noi’s flood network now lies dormant. But when the next disaster comes, the community will re-establish it quickly. “Next time,” Vichain says, “we will be ready.”

Next time may come sooner than the last time. Researchers at MIT and Princeton University have found that the types of superstorms that used to make landfall once a century could now arrive every three to 20 years, and that so-called “500-year floods” might arrive as often as every 25 years, according to findings published in Nature Climate Change. “The volatility of large events of recent years has really grabbed hold of people, whether it’s Bangkok or Japan or Hurricane Sandy,” says Robert J. Sampson, a professor of social sciences at Harvard. “These things have made it clear that we have to think anew about how to prepare for disaster.” Sampson’s work, for instance, involves a method of disaster planning called ecometrics: “Taking the temperature of communities so you know which ones are vulnerable. It allows one to identify breaches of social defenses, not just seawalls,” he says. Like much of the thinking around social infrastructure and disaster preparedness, this is relatively new territory. But Sampson sees it catching on quickly. “There’s been a sea change,” he says. “It’s now on the radar.”

Part of the reason cities like Bangkok and Wellington seem to be catching on to the role of informal social networks more quickly is simply because they have to. “New Zealanders are a scrappier people,” says Dan Neely from the Wellington Emergency Management Office. “We don’t have the level of resources that the U.S. has, so we’re forced to rely on our communities to a degree.”

Vichain echoes this sentiment. “If you expect the government to help you all of the time, you have to pay more in taxes, and Thais aren’t willing to do that,” he said. (This is a city where 150 formal ambulances attempt to serve 12 million residents, after all). Low expectations about government involvement meant that the people of Sai Noi were under no illusions about the level of assistance they would receive. And even if more outside help were available, they told me, it would have been no substitute for the on-the-ground expertise that residents were able to provide as events unfolded. “Based on our experience with the flood, it would work better for us to propose something to the government rather than waiting for them to help us,” says Vichain. “If we want something, we need to stick together and figure it out ourselves.” In turn, the government recognized its limitations and was prepared to cede authority to local networks.

A villager tending a field in Sai Noi.

This last point is salient for discussions about how to empower such informal networks in Western cities, where governments may be less accustomed to letting local actors take the reins. But maybe Western cities are more willing to cede control than one might expect — especially when overwhelmed by crisis. After Hurricane Sandy, when New York was consumed with major tasks like restoring power and subway service, one of the hardest hit neighborhoods, the Red Hook section of Brooklyn, also benefited from one of the most impressive informal responses. A relatively unknown community nonprofit called the Red Hook Initiative instantly transformed, in the words of its executive director, “from a small youth development center into a major hub for the disaster relief effort here.”

With an operation that was thoroughly informal yet, by all accounts, highly efficient and essential, the initiative turned its tiny headquarters into a makeshift storm-recovery center. It provided hot food, cell phone charging (it was one of very few local buildings to keep its power) and perhaps most important, a central command for much of the neighborhood’s flood-relief efforts. In the weeks that followed, the media marveled at the idea that such a rag-tag group could respond so effectively without being led by the government’s hand.

But they needn’t have been so surprised. Even when the sun shines, Red Hook is an unusually isolated neighborhood. It sits on a peninsula, untouched by the subway, and its denizens proudly consider themselves a city apart. Its remoteness seems to foster a shared identity, which felt palpable when residents later talked about organizing their own response in the wake of the storm. “I think many in the Red Hook community feel geographically and psychologically disconnected from the city,” an aide to New York City Speaker Christine Quinn told Capital New York, adding that confronting Hurricane Sandy’s wrath themselves, without top-down intervention, “may have been more empowering for the people of Red Hook than being rescued by a federal agency.”

In Bangkok, how to respond to the next flood is a question that has consumed Visit Hirankitti for the past year and a half. Visit is a professor of engineering at King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology in Ladkrabang, a district in eastern Bangkok that is home to high-tech manufacturing and the crown jewel of the city’s economic ascendance, glittering Suvarnabhumi International Airport. Until recently, though, Ladkrabang served as a catchment for flood waters, a mostly empty plain for the authorities to divert water into during heavy rains.

Visit was in the midst of exams when the flood arrived. Given the area’s history as a catchment, he expected things to get bad quickly. “But the water stopped rising at just above my ankles. This surprised me. I thought it would be much worse,” he says. As it turned out, with Ladkrabang’s recent development as a key economic zone — Japanese heavyweights Honda and Isuzu have factories here, and the airport is the hub of the country’s $30 billion tourism industry — the authorities were desperate to keep the area dry and functioning.

Throughout final exams, Visit was able to come to his office every day. Some of his students, though, were commuting in from harder-hit areas and decided to temporarily relocate their living quarters to the engineering lab, where they had a dry place to sleep and access to food and clean drinking water. Visit and his students watched with alarm as events unfolded across the city. “I became very frustrated. As an engineer, I wanted to do something and not just sit there and watch it happen on TV. I kept thinking, ‘What can I do for the country?’” When he finished grading exams, he recruited several students to stay on through winter break and assist him in developing a system that he hoped would help Thailand cope with future floods.

Engineering professor Visit Hirankitti has been developing a system through which citizens armed with iPhone apps would collect data during floods.

As far as Visit could tell, the key problem had been a lack of information. The authorities never really had a handle on where the water was and, as a result, couldn’t make effective decisions on how to manage it. In addition, Thai citizens, left in the dark, were caught scrambling when the flood arrived. “What I realized was that, as an engineer, I could provide data,” he says. Visit specializes in developing systems that synthesize complex information. His past projects include the country’s first electronic taxi dispatch system and a detailed GIS map of Thailand’s electricity grid. Visit realized that the country’s water management authorities, who were relying on antiquated sensors installed on a few dozen flood gates scattered around the country, needed something similar to respond effectively.

Perhaps counterintuitively, his first decision was to work outside the government, which he believes suffers from a toxic blend of incompetence and corruption. “I didn’t believe in going that route,” he says. Instead, he would rely on the strength of citizen involvement, which had proven to be so decisive in responding to the flood. Visit and his students set out to create a nationwide flood-monitoring system that would rely on thousands of volunteers, creating a vast, cheap, technologically advanced network that could provide up-to-date information to anyone who wanted it, including the authorities. After producing a prototype, he eventually decided to apply for government grants to fund further development.

On a recent afternoon in his lab, which was strewn with computers, tangles of cable and the fast-food-wrapper detritus indicative of late-night research, Visit showed me the version that he believed would be ready next year. The technology was simple: a PVC pipe housing a piece of twine and a small float, a circuit board to collect measurements and a Bluetooth device to transmit data.

Once he’s secured patents for the system, Visit hopes to set up over 1,000 of these sensors around the country. He estimates that they will cost about $30 USD apiece to produce, and he’s currently assessing various funding options, including donations and corporate sponsorship. The sensors will send data to thousands of volunteers who have downloaded a free iPhone app developed by one of Visit’s students. A central server will then collect the data from the phones and generate a three-dimensional map of water levels throughout the country, to be displayed on a public website. When operational, the system will be the largest flood-related network in Thailand. “With the increase in global warming and natural disasters, I have no doubt that another big flood is coming. The question is, what can we do about it? We want to see if people can help people to sort out the problem.”

Since the advent of the smartphone, developers around the world have launched apps designed to help people in crises. Organizations such as the American Red Cross and the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency have created apps designed for emergencies, while privately developed software like BuddyGuard allows users to send out GPS-enabled distress signals. Meanwhile, city governments in urban areas such as Jacksonville, Florida, and Auckland, New Zealand, have created apps that provide real-time emergency information to residents. But Visit’s system is different in that it harnesses the power of users to generate information.

Given the strength of informal networks in Thailand, there is every reason for Visit to feel confident his system will work. Compared to the monumental tasks undertaken by volunteers to save their communities, installing an iPhone app and traveling to within range of a Bluetooth sensor would seem almost trivial. Yet relying entirely on unofficial networks is no solution to the problem, either. Volunteers working together are capable of powerful things, but there are limits to what they can achieve, especially when the authorities and official services underperform.

The view from the Klong Phraya Suren water gate.

I was reminded of this during a morning spent touring the Klong Samwa area with Samai Charoenchang, a former government official. Like Sai Noi in the northwest, Klong Samwa, located on the city’s northeast side, had been submerged in up to two meters of water. Samai drove me around the area in his minivan, introducing me to dozens of people who had joined relief networks. I met a woman who put her lucrative home-based TV production studio on hold for two months to set up a temporary kitchen in her front yard. When running at full capacity with 30 volunteer cooks, she churned out 3,000 free meals per day. I met a man in his seventies who helped deliver that food with members of his local Buddhist meditation center, which had transformed itself into an emergency distribution network. There were many others, and all said that while their networks were currently dormant — there was no flood to respond to — they could be brought back to life within hours.

But there was another, more sinister side to the networks. We stopped at a floodgate that regulates water on Klong Phraya Suren, a canal that runs north to south through Klong Samwa. In early November, at the height of the flood, the gate divided the area into two vastly different worlds. The area on the north side of the gate was completely flooded, while the southern side was dry. The city government, which controlled the gate, had decided to stop the water from flowing south toward central Bangkok, thus flooding the north. Enraged, residents on the northern side organized themselves into a small fighting force and attempted to seize the gate. The southern side responded in kind, and the two met in violent, pitched battles that lasted for two weeks. Armed men on both sides fired shots and fought hand-to-hand with one another before the police arrived and restored order (no one died, though there were plenty of injuries). “By the end, both sides wanted the other to suffer,” says Samai.

Suporn Rujapan in her living room next to a portrait of King Rama V on which the high water mark from the flood is clearly visible.

Regardless of these conflicts, Thais retain faith in their ability to respond to crises informally. Suporn Rujapan, a mother of grown children living on the city’s north side, stayed in her home for the entire duration of the flood. After initially finding herself a victim of the disaster, she quickly grew into a role as front-line leader of her community’s relief efforts, directing government and volunteer resources and becoming a minor media celebrity in the process. During a conversation in the kitchen of her modest concrete shop house, she echoes the thoughts of many Thais I had spoken with. “During the flood, we found that it was better to help ourselves than to rely on the government,” she says. Although she worries that her children’s generation has lost the sense of collective responsibility she feels so deeply, Suporn believes that the country will continue to rely on informal means to respond to future crises. “We’re Thais,” she says simply. “It’s in our nature to help each other.”

“We have to go! We have to go!” Chetsarish Smithnukulkit says, his eyes wide under the silver bangs bouncing on his forehead. Chetsarish was standing in the offices of VS Service, a Thai production company that assists Hollywood film crews with local shoots, recounting the moment when he knew he would get involved in the flood. He didn’t have to take action; the worst of the water was dozens of kilometers away to the north. But Chetsarish’s calculus was simple: “We have the boat. We have the people. We have everything we need to help.”

The boat. Whereas what happened in Sai Noi was hyper-local, a small neighborhood helping itself when no one else could, a story repeated thousands of times across Bangkok, Chetsarish’s experience was different. His is a story of one man’s initiative, and how he marshaled not just his own resources, but also those of large volunteer networks and the government, to help an estimated 2,500 people. But first and foremost, this is the story of a boat.

Chetsarish Smithnukulkit and his crew with the boat that allowed them to aid people in a province north of Bangkok.

“I bought it five or six years ago from a film crew we worked with. They used it to shoot scenes in Rambo 4,” says Chetsarish. “I thought I could use it for another shoot. It didn’t have a motor, so we had to push it around with a bamboo pole.” Essentially a massive floating platform, the barge could hold nearly 50 people and hundreds of pounds of cargo. As the floodwater bore down on Bangkok, he got a call one day from the governor of Ayutthaya, a province north of the city. “He asked us to help. He said they had no food, no water, and that the people were in danger. He told me where to go,” Chetsarish says.

Chetsarish rounded up a crew of young production specialists from his company and student volunteers from a nearby university. But the journey would take hours, even days, if the crew were to push their way, gondola-style, all the way up to Ayutthaya. Chetsarish got on the phone again, this time reaching his friend Major General Adis Ngamchitsuksri, a high-ranking police official. “He said he needed a motor for his boat. I flew one in by seaplane the next day,” Adis says.

For the next two months, working 14-hour days, Chetsarish and his crew traversed the flood-ravaged city in their barge, which played many roles: Floating hospital, search-and-rescue-ship, mobile power station and aid-delivery platform. In coordination with local sources — government, volunteer networks and trapped citizens — they went to places the authorities simply couldn’t reach. They carried a generator that allowed those left behind to charge their cell phones and reestablish contact with the outside world. They transported doctors who provided medical care to the injured. They became a floating morgue, removing several dead bodies.

A woman feeding catfish at the temple next to the Klong Phraya Suren water gate.

They also had some close calls. Ten crewmembers, including Chetsarish, nearly died when they were electrocuted by a submerged power cable. And then there was their fear — perhaps irrational, in retrospect — of crocodiles, hundreds of which had reportedly escaped from illegal farms. “We heard rumors. We though they might be true,” he says, laughing sheepishly now. But the danger mattered little in the face of the overwhelming gratitude they encountered from those they helped. “When we came into an area, everyone stood and applauded,” he says, rubbing his forearms, remembering the goose bumps.

I ask Chetsarish what lessons he took from the flood. He leans in, his voice lowering to a near-whisper. “I have to say something bad about Thai politics.” The country’s two parties, in perpetual conflict, were not equipped to handle the crisis. “They look after themselves and not the people,” he says. “And besides, we’re ten times more efficient. The police had no way of helping people. That’s why they needed me.” On this last point, Major General Adis agrees. “We’re always ready to go to the public for help. We knew we couldn’t do this alone.” When the next flood comes, Adis will get on the phone and call his friend Chetsarish, the man with the boat. “The engine is working. I just checked it a couple of days ago,” Chetsarish says. “We’re ready to go.”

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Dustin Roasa is a journalist based in Cambodia. His writing has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Guardian, Foreign Policy and Dissent, among others.

Giorgio Taraschi is a 26-year-old Italian photographer currently based in Bangkok. His work has appeared in the Guardian, Internazionale, Courrier International and GEO, among others.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine