Studies that connect green space to mental health and wellbeing abound. And this connection is intuitive—people have long retreated to parks and natural places to recharge from the pressures of daily life. Less known is the fact that greening is gaining recognition as an effective violence prevention strategy.

Greening vacant lots, revitalizing parks and recreational areas, and creating new green spaces has multiple benefits. Communities that implement greening can improve mental and physical health outcomes; reduce stress, aggression, and the incidence and severity of psychiatric conditions; increase social interaction; enhance childhood development and minimize stormwater runoff. And, research shows, greening can reduce and prevent violence, especially when it’s part of a comprehensive prevention strategy that distributes the work across sectors — when community developers, public health practitioners, and community residents come together to design the green space, this is when the most positive impact can be realized.

The proof is in the greening

In 2018, researchers in Philadelphia partnered with the community to convert vacant lots into small parks as part of a violence prevention strategy. The city contains over 44,000 vacant lots, many located in low-income areas. Researchers randomly assigned over 500 of these lots to three groups. The first group of lots were cleaned and “greened” with vegetation, the second set were just cleaned, and the third were left untreated. The first two groups of lots that received treatment had significant decreases in crime and violence. (The researchers hypothesize that sprucing up vacant lots removes the perception that nobody cares about a neighborhood. The new lots also create a new place for people to congregate, resulting in more “eyes on the street.”) Results were especially impressive in areas where residents’ incomes were below the poverty line.

A Chicago study that involved 145 women living in public housing found that exposure to green surroundings reduces mental fatigue and improves the ability to concentrate and willingness to handle problems more deliberately and less aggressively. Of the women interviewed in this study, those living near trees and green spaces reported less aggression and violence than did those living in park-poor areas. Chicago is now following the Philadelphia model, recruiting people who’ve experienced and perpetrated violence to revitalize vacant lots.

The same Chicago study found that even adding just a few trees helped residents feel safer. Similar findings were revealed in a 2012 study done in Portland, Oregon—the presence of trees in public streets correlated with decreased violence.

Greening on the ground

Programs nationwide are developing greening efforts to reduce violence. The Michigan Coalition to End Domestic and Sexual Violence has a multi-year plan to prevent gender-based violence through greening tactics in Detroit, Kalamazoo and Houghton County. The coalition supports community-led greening initiatives like planting urban gardens, renovating parks, and improving safety and maintenance of green spaces.

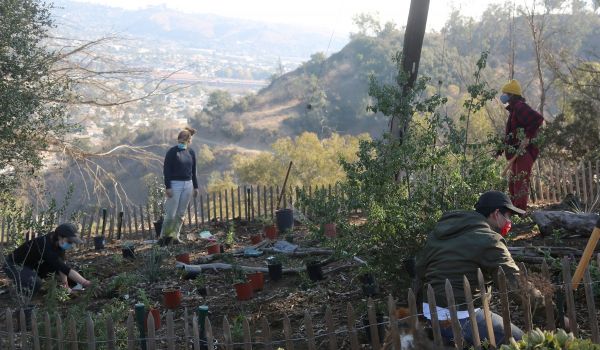

In East Salinas, California, Building Healthy Communities and the Monterey County Health Department engage residents to address poverty and housing instability, lack of social connection, and high rates of violence affecting youth. They believe that fairly investing in the community in ways informed by residents helps get to the root of the problem.

Addressing safety concerns in East Salinas meant improving lighting, trimming greenery to improve visibility, transforming neglected public spaces, encouraging people to come outdoors to participate in community events, and creating art to foster a sense of belonging and pride in the community.

As a result of changing the look and feel of public spaces, neighbors feel safer and more comfortable using green spaces to connect with one another. This has created a positive feedback loop — when people feel safe and welcome in community parks and green spaces, this increases social connection and reduces fear. This coalition’s work highlights the value of increasing access to green space and ensuring that existing green spaces are safe and usable.

Many efforts to reduce violence through greening focus on low-income communities and communities of color because those communities have less access to green spaces. Historically, community developers have created parks and green spaces in affluent neighborhoods rather than in urban low-income communities and communities of color that experience segregation and disinvestment. In Los Angeles, for example, 45 percent of communities that are home to low-income Latino and African-American residents are park poor. These under-resourced communities that lack green space are at greater risk for social disconnection and have lower perceptions of safety.

The future is green

Los Angeles County also offers an example of how communities can take greening into their own hands. In 2016, the county overwhelmingly approved the Safe, Clean Neighborhood Parks and Beaches Measure, which is expected to generate $95 million per year. This funding will make a real difference when it comes to addressing inequities in park funding and upkeep in LA’s park-poor communities. Significant credit for this victory is due to the Park Equity Alliance, a group of social justice organizations, environmental groups, health equity advocates, and others. They made sure the LA board of supervisors supported equity provisions to ensure that funds generated by Measure A are prioritized for projects in high-need areas.

This story was co-published with the Build Healthy Places Network. Read it on their site here.

Danielle Bowen-Gerstein is a current senior studying at Macalester College in Saint Paul, Minnesota. She is a Geography major with a concentration in Community and Global Health. This past summer, she interned at Prevention Institute, where she explored a range of topics related to community health. She is particularly interested in issues of health equity and how environmental characteristics and neighborhood features such as green space can influence health outcomes.

Christine Williams is a multimedia specialist on the Communications team at the Prevention Institute.

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)