Today in New York City marks one of the most contentious, emotionally-charged city council votes in years. It’s a vote on whether to approve a plan to build four new jail facilities across four of New York City’s five boroughs. The city and its supporters have billed it as its plan to close Rikers Island for good, replacing it with the four new facilities. But as opponents have pointed out, nothing in the plan actually commits the city to closing Rikers.

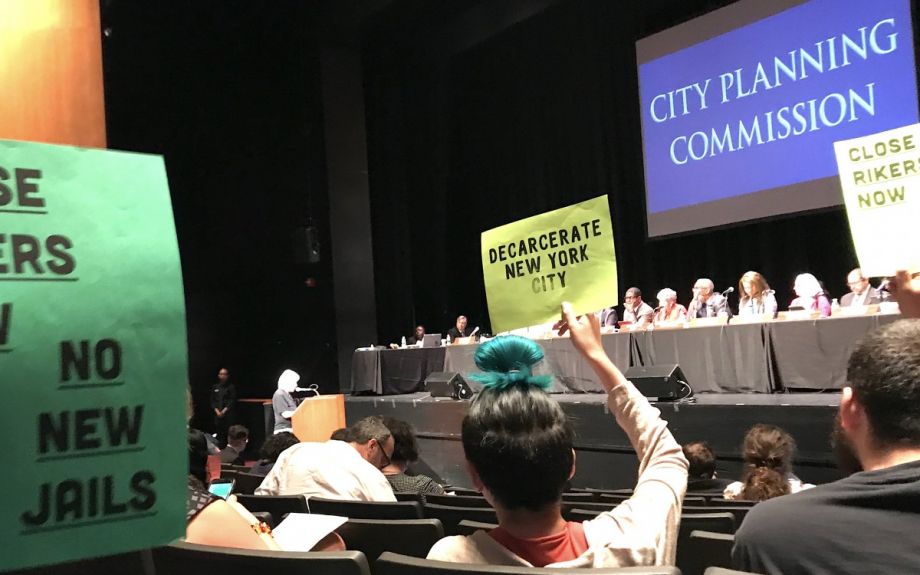

Regardless of the final tally, the last few months have seen meetings and hearings at the neighborhood and citywide levels packed with vocal opponents as well as supporters of the plan.

The city’s Department of Corrections and its supporters continue to argue that it would not be possible to close Rikers Island’s jail facilities without building the new facilities, at a cost of $8.7 billion — though the city still has not released a specific construction timeline or final designs for the jails. In response to community concerns, it continues to tweak the design outlines up until the last minute, mainly reducing the height of the four vertical jails.

Opponents, primarily organized under the banner of “No New Jails NYC,” have shut down meetings at least momentarily on several occasions. They don’t trust that the city will ultimately close Rikers Island after building the new facilities. Three of the four new facilities will replace and expand the capacity of current jails, meaning that those inmates would be transferred to Rikers in the meantime.

It was a “No New Jails” sign near their office that drew Sabrina Bazile to volunteer their time handing out fliers for the group in advance of an earlier hearing on the plan hosted by Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer. An urban planner by training and profession, they soon connected with fellow urban planner Sylvia Morse to draft an open letter from “urban planning and policy practitioners, professors, and researchers” in support of the No New Jails campaign. Similar open letters have been penned by professionals with their own perspectives on mass incarceration, including public health and legal professionals.

The urban planning letter garnered more than 250 signatures, from planners or planning-adjacent professionals across the country.

“Urban designers, architects, planners, we all have a role in shaping cities and incarceration as a topic is part of that,” Bazile says. “It’s not something that’s separate, it’s something that should be talked about and addressed the planning community.”

Professional planners were already involved, Bazile points out, in drafting the city’s plan and various documents in support of the city’s land-use review application to approve zoning and other land-use changes required to build its new jail facilities at each of the four sites.

“We’re not trying to make connections between planning and incarceration, we’re acknowledging that they are there and there are many folks in the profession who see that,” Morse says. “Planners had to work on this thing, planners had to do the environmental review, so we can’t pretend we’re not part of this.”

The letter calls for closing the jails on Rikers Island without building new jails “by embarking on a community-based abolitionist planning process” — such as the process No New Jails itself underwent to come up with its own plan to close Rikers.

Th No New Jails plan calls for the city to marshal resources it might spend on building jails to instead fund the backlog of repairs in the city’s public housing; improve shelter conditions; expand comprehensive community-based and culturally-responsive mental health resources; harm reduction programs; and access to education especially for people who have experienced incarceration. It also calls to end mass surveillance and the extraction of wealth from communities through criminal court fines, fees, surcharges, and bail; and stopping false and illegal arrests. The plan envisions that these resources will continue what has already been a significant decline in NYC jail admissions over the past decade.

The number of people in jail in NYC has declined 67 percent from its 1991 peak, and 39 percent since Mayor Bill de Blasio came into office. Jail admissions have declined 50 percent since 2014. The city already has the lowest incarceration rate among all large U.S. cities. As part of the broader abolitionist movement across the country, No New Jails believes its plan will help keep those numbers moving in a downward direction to eventually close Rikers Island without having to build new jails.

“One of our goals with the letter is to normalize the conversation, to have an advocacy tool for planners to say look abolition is not a fringe position to take, it is within the purview of planning,” Morse says.

As the open letter points out, existing bail and pretrial detention reforms and diversion programs in the city are reducing the jail population faster than the city projected. Some 72 percent of the city’s jail population are there because they could not afford to post bail at their arraignment. State bail reforms going into effect in January 2020 will significantly reduce the number of people entering jail for misdemeanor and non-violent charges, reducing the daily jail population by up to 3,000 people — bringing the jail population to approximately 4,000 people per day within a year or two, that much closer to striking distance of closing Rikers Island without needing new jails. The city’s existing borough-based jails can hold around 2,400 inmates.

The city and its supporters, which include individuals formerly held in detention on Rikers Island, argue that the newer facilities would be more humane and safer than current Rikers Island or current borough-based facilities. But to the planners who have signed this open letter, any jail is by definition inhumane.

“Foremost, we are opposed to the caging of human beings in jails, a practice widely evidenced to enact violence against Black and Brown people regardless of location or design,” the letter reads. “The City’s proposal for ‘humane design’ in new jails is part of a long reformist tradition that has promised rehabilitative jails and consistently failed … design cannot be humane in an inhumane system.”

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)