On July 12, 1967, Newark police beat a Black taxi driver before wrongfully arresting him for assault. Six days of uprising against the city’s police followed. During what was ultimately called the Newark Rebellion, 26 people were killed and arrests and injuries proliferated across Newark’s Black community.

Little improved in the decades following. Finally, after an ACLU petition, in 2014 the DOJ found that 75% of police stops in the city were illegal and 20% of reported uses of force were unreasonable. As a result, the DOJ and the city entered into a still-ongoing consent decree in 2016 to reform Newark’s police department.

Since then, some progress appears to have been made. In 2020, the Newark police didn’t fire their weapons at all. One group thinks they might have had something to do with it.

“Trauma to Trust has been a game changer in the city in terms of not just looking at ways to train [people], but to shift the culture and be able to have the uncomfortable conversations,” says Keesha Eure, a clinical social worker and community activist who has participated in and facilitated Trauma to Trust trainings.

Trauma to Trust is an initiative of Equal Justice USA, a national organization working to break cycles of trauma and violence. Since 2016, Trauma to Trust has facilitated trauma-informed trainings that bring Newark police officers and community members together. The multi-session program aims to foster a mutual understanding of trauma on both the community and police sides of the community safety equation. Eure says that police who have gone through the 16-hour, two-day trainings understand the “need to be more empathetic, have more compassion, and not be so aggressive. [They’re] more understanding that although people commit acts of crime, they’re still people and need to be treated with humanity and decency.”

Through 2019, EJ USA has run more than 26 full trainings that over 500 people have completed, 224 of which have been police officers. The group spent most of 2020 creating a virtual primer in response to the pandemic, a lighter version of the training. Since it launched three months ago, 94 community members and police officers have taken the virtual primer—and it’s beginning to show.

“We ran some numbers in 2018 to track the progress of officers who took the training and there was a nearly 50% decrease in civilian complaints against officers who have taken our training compared to before, which is incredible,” says Lionel LaTouche, director of the Trauma to Trust program.

EJUSA’s thinking around Trauma to Trust started with a simple question: “What would it look like if Newark was a trauma-informed city? That began to inform the drive behind what the bones of the curriculum would look like,” LaTouche says of the inception of the program. “It’s about not looking at someone and saying, ‘What’s wrong with you?’ but ‘What happened to you?’” he adds.

Today, the program covers everything from a working definition of what trauma is and how it shows up differently in different people to the epigenetics of trauma — how it can be passed down through generations from parents to children. The program finds community members who want to participate through outreach—they create fliers and draft emails that are then shared with community organizations which pass the information onto the people they serve.

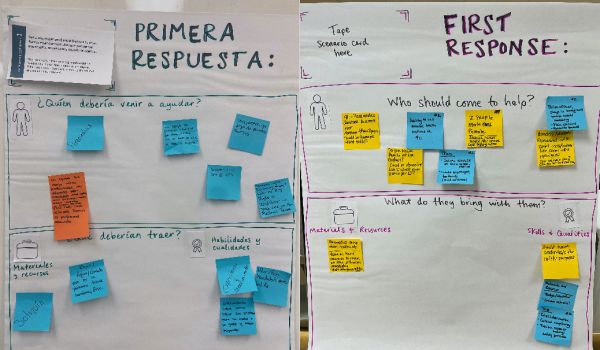

The capstone of the training is a visioning session where police officers and community members are teamed up to imagine what a trauma-informed city looks like, coming up with ideas like a central hub where community members can access a range of resources and social services all in one place. As a result of training sessions, in April 2019 the Newark Police Department established a new policy for interacting with members of the LGBTQ+ community that outlines gender classification procedures and more while establishing the appointment of an LGBTQ+ Liaison, a position that was filled in March of this year.

The key is that it’s not a one-way street. The training helps community members understand the trauma that cops experience as well. “When you hear community members vouch for the mental well-being of police officers, you can’t put a price on that,” LaTouche says.

The hardest part has been finding police officers who are willing to not just attend, but authentically engage, Eure says.

There are “officers who don’t like the trainings and think it’s a bunch of crap,” Eure says, adding that they’ve had more success with younger, newer officers. “I’ve seen officers—the ones who are committed to change and who are community-based—make changes,” she says.

Another issue is the inherent power imbalance between officers and community members. Officers are on the clock and getting paid while community members are there on their own time and dime. As a result, officers wear their uniforms to the trainings. “I always fight, I don’t think they should wear their uniforms,” she adds. “They have to come as people.”

As with all progress, there’s still a long way to go.

“It’s a big deal that the Newark Police Department reported that there were no police involved shootings in 2020,” says Yannick Wood, the director of the criminal justice reform program at the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice. However, he cautions that it’s much too soon to tell what the real cause was, especially because the pandemic required many to simply remain at home for most of last year. And NPD’s streak of no weapon firings ended brutally on New Years Day of this year, when Carl Dorsey III, 39, of South Orange, was fatally shot by Newark Police Detective Rod Simpkins.

Wood wants to see more community-involved work like Trauma to Trust. He’d also like to see a civilian complaint review board established. “The only way to investigate complaints against an officer is if you have substantial power and can compel the officer to show up and be able to subpoena documents,” he says. “After that, if the complaint is substantiated, there needs to be some kind of disciplinary mechanism, some sort of consequence. It’s through that that I believe there could be true accountability between the police and the community.”

Cinnamon Janzer is a freelance journalist based in Minneapolis. Her work has appeared in National Geographic, U.S. News & World Report, Rewire.news, and more. She holds an MA in Social Design, with a specialization in intervention design, from the Maryland Institute College of Art and a BA in Cultural Anthropology and Fine Art from the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities.

Follow Cinnamon .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)