During Paul Conley Briley’s time in a San Francisco jail a few years ago, one of the hardest parts was not talking with his family as he sought to spare them the cost of expensive prison phone calls.

“If an incarcerated person made two 15-minute calls a day, it would have cost $300 over an average 70-day stay,” he said. “I knew they didn’t have the money.”

It did not stop there, he said, pointing to the sky-high prices U.S. prisoners pay for basic items like soap, as well as a long list of fees charged by courts and jail authorities that can leave inmates and their families in debt for years.

Today, Briley is a regional coordinator for All of Us or None, a nonprofit that advocates for the incarcerated and their families across the United States, where there is growing debate about the often unequal impact of common fees and fines.

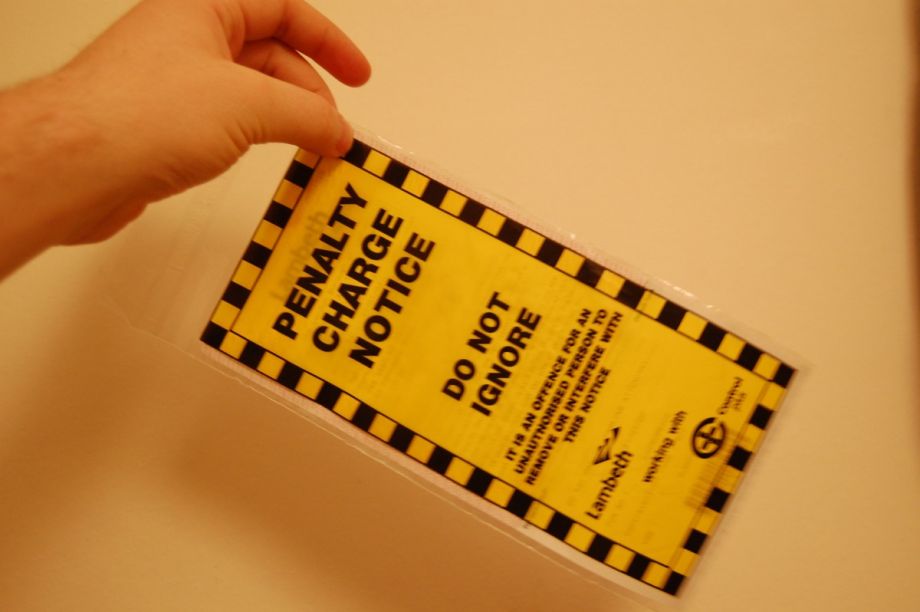

From parking tickets to library fines, such levies have faced increased scrutiny due to the pandemic and anti-racism protests, and hundreds of local reforms have been enacted, according to monitoring by the Fines and Fees Justice Center.

Last month, participants from more than 50 U.S. cities and counties gathered for a first-ever “bootcamp” event aimed at sharing lessons and plans, said Joanna Weiss, co-director of the advocacy group.

“Fines and fees are a problem everywhere, and it’s remarkable … how many places are hungry to address this problem,” she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

‘High Pain, Low Gain’

Much of the momentum stems from a 2015 report into the killing of Black teenager Michael Brown, who was shot dead by police in Ferguson, Missouri.

A Justice Department (DOJ) report found Ferguson’s police department was getting almost a quarter of its budget from fines and fees — a city-wide revenue strategy that was not only racialized, but was “shaping” policing practices.

“That report showed that when you take a poor community and try to use this method to fill budget holes, you’re trying to get money from the poorest members of the community,” Weiss said.

More than a third of Americans may have difficulty covering a $400 emergency expense, the Federal Reserve found last year, meaning a fine, compounded by late fees, can leave a family in dire straits.

In Ferguson, unpaid fines also quickly turned into arrest warrants to collect them, the DOJ found, with more than 16,000 people having outstanding warrants in late 2014 — in a town of 21,000.

Subsequent studies found such problems went far beyond Ferguson, Weiss said.

San Francisco was one of the first places to confront the problem, scrapping all administrative fees in its criminal justice system in 2018, said Anne Stuhldreher, director of the San Francisco Treasurer’s Financial Justice Project.

That covered fees for probation, pre-sentencing reports, ankle bracelet rentals and more, and saw the city write off $32 million in debt owed by 21,000 people.

With help from Briley and others, San Francisco also made jail phone calls free — prompting call volumes to jump by 40% — and banned revenue generation from products or services for incarcerated people and their families.

A federal bill currently under debate would strengthen regulators’ ability to crack down on “unjust and unreasonable” prison phone charges.

“A lot of this is ‘high pain, low gain’,” Stuhldreher said.

San Francisco also was a pioneer in halting the suspension of drivers’ licenses for unpaid traffic tickets, prompting 22 states and Washington D.C. to follow suit and sparking a federal proposal.

“At a time when the COVID-19 pandemic has made it even harder for Americans to pay their bills and care for their families, taking away someone’s driver’s license can make it nearly impossible to hold down a job and therefore pay back their debts,” Senator Chris Coons said in a statement.

Coons is the author of a bill that would ban suspending a driver’s license for non-payment of a civil or criminal fine or fee.

Holistic Assessment

It is not yet clear how such reforms will affect cities’ revenue, said Anand Subramanian, managing director of PolicyLink, a nonprofit.

“In some places it actually increases, and in some places it doesn’t. But nobody has really done a holistic assessment,” he said, noting many cities and counties are ill-equipped to evaluate revenue from fines versus collection costs.

PolicyLink organized last month’s “bootcamp” event, in part to introduce officials to the need for such audits.

Local officials have been more open to re-examining fees than fines, which some see as serving an important punitive function, Subramanian said, even as there is little evidence they guide public behavior.

Such opposition was seen in St. Paul, Minnesota, which eliminated library late fines starting in 2019, triggering angry reactions as if “the sky was falling, with conversations around personal responsibility,” recalled Muneer Karcher-Ramos, director of the city’s Office of Financial Empowerment.

But the positive impact of scrapping the fines was immediate, he said, with 40,000 patrons returning to St. Paul libraries in the first three months. Among people of color, numbers rose by double digits.

Buoyed by the experience, city officials went further when the pandemic struck — eliminating water shutoffs, waiving vehicle towing and impound fees and halting the collection of old debts.

The end result is a broad cultural change across the city’s government, Karcher-Ramos said, with officials regularly questioning remaining levies and their impact on equity.

“Has it changed the way we think about things in St. Paul? Absolutely,” he said. “It’s a conversation all the time now.”

This story was originally published by the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers the lives of people around the world who struggle to live freely or fairly. It appears here as part of the SoJo Exchange from the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous reporting about responses to social problems.

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)