Theo Deutinger used to like the park in front of De Nederlandsche Bank in Amsterdam. Trees along the sidewalk shield the building from the street. Between them are big boulders that continue into the crosswalk, marking off bike lanes from tram lines and traffic.

Then Deutinger learned the rocks were placed there to hinder bank robbers. They prevent cars from getting too close.

“Now I’m ruined. Whenever I see something, I always look what is behind it,” says Deutinger, an architect, writer, and designer who splits his time between Austria and The Netherlands. “I don’t trust landscape anymore.”

He doesn’t want us to trust it either.

Deutinger’s recent book, “Handbook of Tyranny,” illustrates the ways political power, authoritarianism, and control can manifest in the design of our cities.

Deutinger calls it a “collection of examples of how design is against humans, or against our freedom of movement.” Like those rocks at the bank.

Now, an exhibition at the Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York City is bringing Deutinger’s observations directly into conversation with Lower Manhattan.

The gallery space on Kenmare Street is showcasing seven categories of design that restrict human movement or exert control. Walking tours invite the public to see these technologies in action along the “Tyranny Trail.” The walking route links 11 sites in Lower Manhattan where surveillance and control can be witnessed in the landscape, from Zuccotti Park to the US Court of International Trade.

Deutinger says he hopes the project makes people aware of the hidden barriers built into their environments, as he became aware during his research.

“As an architect … I assumed we are educated to serve the people and with everything we do we contribute to a better world. By going deeper into this subject I realized there is a lot of design that does the opposite,” he says.

“Of course it’s naive to think that everything we do is serving the better, but still from architecture or design I would not have imagined such cruelties.”

The “Tyranny Trail” stretches from the gallery to the 9/11 Memorial.

On the way, it stops at the New York Stock Exchange, a landscape that was totally surprising to Deutinger. The national bank in the Netherlands, whose park he had admired, uses a subtle form of restrictive design: the “green fortress”, natural elements that restrict movement.

The New York Stock Exchange uses far more aggressive tactics. Traffic is forbidden in three so-called “frozen zones” around the building, enforced by guard posts and wedge barriers sometimes used in counter-terrorism efforts.

“There is a feedback from the wars Americans fight and bringing their technology home,” says Deutinger. “Lower Manhattan looks like a war zone to me.”

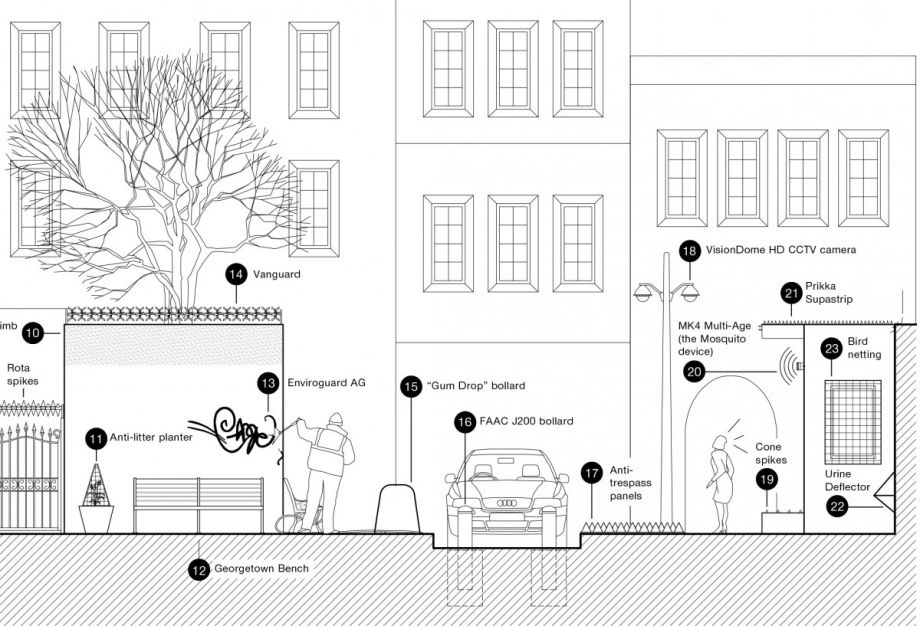

Some of the structures that exert control, as depicted in Deutinger's book. Many of these structures — the high-frequency sound emitter, spiked surfaces, and benches with armrests down the middle — could also be termed hostile architecture. (Courtesy Theo Deutinger)

Tours on April 19th and 20th were led by photographer John Michael Kilbane, a photographer who has documented hostile architecture. An upcoming tour on April 26 will be led by Rebecca Manski, a researcher specializing in the history of the Wall Street area since her involvement in Occupy Wall Street. Zuccotti Park, where protesters encamped, is a stop on the tour. Visitors can also walk the route on their own with a map from the gallery or online.

The accompanying exhibition, “State of Tyranny,” prompts visitors to think beyond physical architecture. It begins with a design element that’s not self-evidently about design at all: the passport.

“With the passport we got the benefit of traveling but also the limiting of visiting states or other nations,” says Deutinger.

He says we can think of the world like a palace with 203 rooms, one for every country. A person with an American passport can enter 184 of those rooms without a travel visa, or with a visa on arrival. A person with an Afghani passport can enter only 30 of those rooms.

“The size of the world can be so different, so for some people it’s a very small world and for others it’s a very big world,” says Deutinger, whose Austrian passport grants him access to 185 rooms.

“We who invented the passport have a very big world, and those who have to live with our invention, for them it’s better to throw it away.”

The exhibition displays objects from seven categories of restrictive design, including borders and fences, crowd-control devices, prisons, and hostile architecture like benches designed to discourage homeless people from using them. Even gravel pathways, which loudly announce someone is approaching, is a form of control, Deutinger says.

One of the more surprising examples to Deutinger: acoustic controls. Like the high-pitched sonic devices some business owners have installed to prevent teens from loitering outside — only young people can hear the frequency. Or long range acoustic devices that aim to dispel protestors from public spaces through painfully loud or disruptive noises.

Deutinger sees this as an example of how tyrannical design is getting “more refined”: Acoustic weapons leave a much less menacing visual record than water cannons.

“This abundance of cameras and video cameras changes also the tools of police,” says Deutinger. He predicts more and more invisible tools — like ways to cut off cell phone reception to a particular area — will come to define the restrictive design of the future.

For now, there are still many ways to see tyrannical design in action — just a short walk from the Storefront for Art and Architecture.

Jen Kinney is a freelance writer and documentary photographer. Her work has also appeared in Philadelphia Magazine, High Country News online, and the Anchorage Press. She is currently a student of radio production at the Salt Institute of Documentary Studies. See her work at jakinney.com.

Follow Jen .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)