Native American people march to bring awareness to the MMIW movement. (Photo by Matthew S. Browning / Real Change News)

Matthew S. Browning

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberDays after it was enacted on July 1, Washington’s new Missing Indigenous Person Alert (MIPA) was put to the test following the Fourth of July weekend.

Gracie J. Williams, a 14-year-old member of the Makah Tribe, had last been seen in the Five Corners neighborhood of Burien, a city in King County less than 11 miles south of downtown Seattle. She could have been the first name ever announced by the MIPA system, designed to address an ongoing crisis of Indigenous peoples, especially women and girls, being assaulted, abducted and murdered at alarmingly disproportionate rates.

That reality frightened the Williams’ family, activists and state officials, all of whom insisted that issuing an alert was the right course of action at a moment where a vulnerable Indigenous teenager’s life may have been on the line.

Despite meeting requirements to do so, local police ultimately decided against broadcasting her identity through the statewide MIPA system, which is run by the Washington State Patrol and also produces Amber and Silver Alerts. “If she was a little white girl, or just anybody else, maybe it would have been different,” says her mother, Lori Williams Holden.

The Burien case, which has not been previously reported, offers a window into one city’s complicated decision-making process when responding to the disappearance of a Native girl. It also illustrates the urgent need for law enforcement agencies across the state to better understand the alert system, Indigenous advocates say. Despite the passage of landmark legislation, which allocated funding and resources for the newly upgraded system, advocates also say police are still unprepared and ill-equipped more than two months after its implementation.

Williams Holden sprung into action when she discovered that her daughter ran away in the early hours of July 6, upon returning from a trip to California. The Makah mother disciplined her daughter, punishing her by revoking cell phone privileges and removing the bedroom door from its hinges.

Lori Williams Holden (left) and her daughter Gracie are members of the Makah Tribe. (Courtesy photo)

It had been a year since the family moved back to the Seattle suburbs from Neah Bay, a coastal community nestled on the Makah homelands overlooking the Salish Sea and the Pacific Northwest. That’s where Williams earned a reputation for running away, even two years ago at the age of 12.

“Something was a little off. I wasn’t too sure what it was. She was just saying, ‘I love you’ and gave me hugs, and I was like, ‘that’s kind of weird,’” Williams Holden tells Next City. “So, I was kind of nervous about going to sleep.”

When Williams Holden woke up to find the 14-year-old missing, she notified Burien police around 4 a.m. that her daughter is Indigenous. That missing person report then would’ve been sent, in theory, to the new MIPA system in Olympia by the Burien department. Instead, the report ignited a back-and-forth debate between law enforcement agents and state officials over whether the voluntary alert tool should be implemented for the first time.

Burien Police Chief Ted Boe and his team wrestled with the decision in the hours and days after the teen’s disappearance. “It was an intentional decision at that point, to not launch it,” Boe tells Next City. “And if that didn’t work, we fully intended to launch it if we failed.”

Patti Gosch, an Olympia-based tribal liaison at the Washington State Patrol, was in frequent communication with the family throughout the ordeal. She’s responsible for responding to incidents in the east. Her colleague Dawn Pullin, another tribal liaison, manages the west in Spokane. Splitting the entire state in half, the pair handle calls from the concerned families of Indigenous peoples who go missing — regardless of whether they’re runaways.

“I think that had the alert been out, it would have been much more effective. This is a learning curve,” Gosch says. “There were a lot of agencies involved that were toeing the line.”

The 2018 Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women's March in Seattle. (Photo by Matthew S. Browning / Real Change News)

The several steps to release a statewide alert once took an entire day of coordinating with families, law enforcement agencies, grassroots organizers and the news media. Now, when done right, it can be accomplished in less than 10 minutes, Gosch says.

Williams’ missing person report, obtained by Next City through the King County Sheriff’s Department, reveals that Gosch emailed Burien about that streamlined process after being contacted by the Williams family.

Gosch asked whether their agency would be interested in issuing an alert, noting that a special agent at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, part of Interior Secretary Deb Haaland’s Missing & Murdered Unit, had also offered assistance on this search.

But local police declined. Williams’ disappearance did not “appear to qualify for an alert, if I am assuming correctly that it has the same criteria as an Amber Alert,” an official from the King County Sheriff’s Department replied. Burien police later agreed with the county official’s assessment.

But the MIPA alert has its own distinct set of minimal reporting standards which are easier to satisfy, separate from Silver or Amber Alerts that the state patrol also produces. The new alert can be activated as long as the missing adult or juvenile is identified as an Indigenous person when their case is created and uploaded to the FBI’s National Crime Information Center.

It wasn’t easy for Gosch to idly wait as grassroots searches were already underway. Williams had a documented history of depression and attempted suicide, the report added.

“This case was very difficult for me as the liaison. It was ugly. It was very difficult to not be able to do more than what we were able to,” Gosch says. “I would’ve gone to get my car and go find her.”

Dawn Pullins (left) and Patti Gosch serve as the Washington State Patrol’s tribal liaisons, state-funded positions created through a legislative act passed in 2019. (Photo courtesy of Washington State Patrol)

Tribal liaisons at the Washington State Patrol are put in tough positions on a daily basis, working between the families of missing loved ones and the law enforcement agencies that are supposed to find them.

“We’re a clearing house; we don’t have any jurisdiction over any of these missing persons,” Pullin says. “What Patti and I do is we can help bridge those gaps in communication between families and law enforcement.”

Gosch’s concerns were echoed less than a day later by Annie Forsman-Adams, a policy analyst at the Attorney General’s Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People Task Force. She also consulted Burien police, ensuring their department was aware that MIPA went into effect only a week after her disappearance.

When local police reiterated their reasoning for why the alert system wasn’t applicable in this instance, Forsman-Adams clarified that a missing Indigenous person didn’t need to be in danger for an alert to be created. Activating the alert may have even expedited the search to locate her sooner.

For the second time in less than 48 hours, the department contemplated publishing a MIPA — and ultimately decided against it. But Burien strategically sent out an internal Crime Analysis Unit bulletin to a few agencies, since their intel placed Williams approximately within their jurisdictions.

Police chief Boe says he worried that immediately publishing a MIPA may compromise their leads, cause her to flee and potentially endanger her safety. At the time, the afflicted family also supported that decision.

Williams was also feeding occasional updates to her friends through Snapchat on a borrowed cell phone. That channel of communication through the social media app served as a “lifeline,” police say, and was another reason why Burien didn’t activate a MIPA out of fear of losing her for good.

“We really did have momentum in this investigation, and I do support at least the thought process that went into this was continually moving towards getting her home,” Boe says of how the city handled Williams’ case. “I think that was the mindset that we were at from the start of this — getting Gracie home was our first priority. We were trying to do the best we could to deploy the right tools at the right time.”

Williams’ family couldn’t simply wait and hope for her to turn up. They shared the news on social media and passed out flyers. Countless pictures of the smiling young girl were popping up on social media platforms. Makah elders rushed to lend a hand in searching for one of their lost daughters.

Roxanne White created the first missing poster for Gracie J. Williams through her self-funded grassroots organization, Missing, Murdered Indigenous Women People & Families. (Courtesy photo)

Scouring groups of grassroots search parties are all too familiar in Washington due to the endemic disappearances of Indigenous peoples in the region. It’s considered an essential network, especially by the Washington State Patrol, which relies on these organizers to spread the word. The search parties are often even able to find missing persons before law enforcement agencies do.

They eventually recovered her without a police escort when a Native search party consisting of Williams’ parents and a few friends tracked the teen to Olympia, more than 50 miles away from where she reportedly went missing. Williams is now back home after a visit to a nearby hospital in Olympia. And her mother says Williams doesn’t remember much from those few days, raising concerns over whether she may have been under the influence of narcotics.

It’s been a distressing ordeal felt by the entire family, one that may haunt them for years to come. But Williams Holden is simply happy that she got her daughter back alive — unlike hundreds of other cold cases where Native Washingtonians disappear and never return. And the mother didn’t hesitate to share their deeply personal affair with Next City in the hopes that other parents and law enforcement agencies can learn from their struggle as well.

“This could have been avoided,” Williams Holden says. “What can we do better for the next kid to make this a little bit easier for the next mom, dad or family?”

The 2018 Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women's March in Seattle. (Photo by Matthew S. Browning / Real Change News)

It didn’t take long for Washington state lawmaker Rep. Debra Lekanoff, a member of the Tlingit Nation, to learn about the Burien incident, albeit indirectly. She sponsored the bill to create the very same alert system to find their Native daughters and sons.

Her first-in-the-nation legislation, passed earlier this year, has been in effect since the beginning of July. But these past several weeks have been like growing pains for the only Native American sitting among the state’s 147 legislators.

The state’s Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People task force offered a series of recommendations for the Washington State Patrol in the days, weeks and months ahead of its highly-anticipated start date. This guidance included multiple emails, phone calls and advising for initial consultations with each of the 29 federally-recognized tribes scattered across the state.

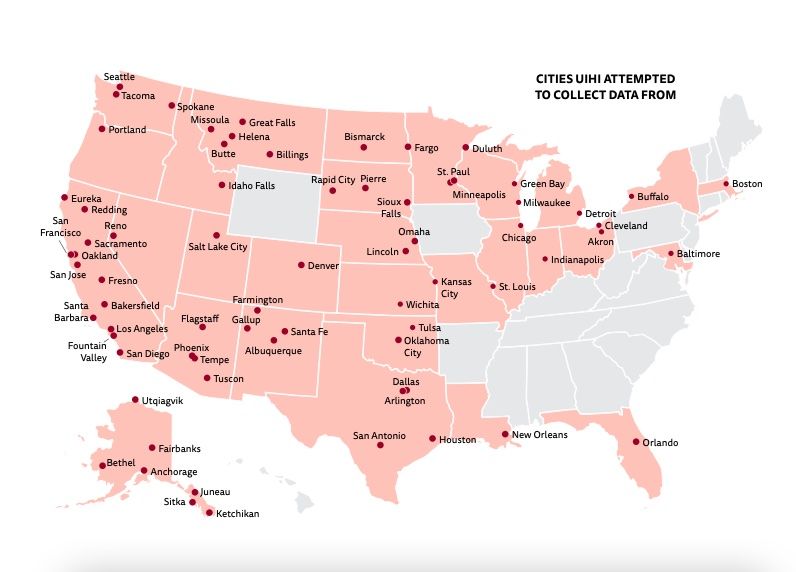

Increased engagement with urban organizations, including the Seattle-based Urban Indian Health Institute (UIHI) were intended to enhance awareness of this new tool for law enforcement. Lekanoff, one of the task force’s 23 sitting members, says their four key priorities were “consult, engage, communicate and educate.” But she says the state’s efforts to do so fell short.

“Washington State Patrol has still not consulted with the tribes,” Lekanoff tells Next City. “They rolled out the (MIPA) alert system without taking any of those steps.”

The optional MIPA training sessions with tribal and non-tribal law enforcement agencies didn’t start until July 11, Gosch says.

“If this alert has done anything it has brought awareness and attention to the need to educate law enforcement and the public to the unique struggles of reporting someone who is identified as Indigenous as missing,” says Carrie Gordon, director of Washington State Patrol’s Missing and Unidentified Person Unit. “We will continue to offer training and outreach to law enforcement around the state, not just tribal agencies but all law enforcement to continue to spread awareness and improve processes.”

A 2018 report by the Urban Indian Health Institute identified 506 cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in 71 cities throughout 29 states. The researchers consider those findings to be “likely an undercount” in urban areas. (Graphic courtesy UIHI)

Abigail Echo-Hawk, director of UIHI, has been sounding the alarm on this issue for years. “There’s always room for improvement, and more work could have been and needs to be done as they move this forward,” she says.

A 2018 report she authored shows Seattle is the nation’s leading city with the highest number of reported Indigenous homicides across their 71 cities sampled. The report also highlights how “poor relationships between law enforcement and American Indian and Alaska Native communities,” on top of underreporting, racial misclassification and poor record-keeping protocols, contribute to the “likely undercount of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in urban areas.”

“I was not surprised at all, and I wish I hadn’t,” says Echo-Hawk, a citizen of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma. “The reason that we did this report is not because our communities didn’t know, it’s because we all knew and nobody listened to us. I’ve been telling them this is an issue for years.”

Echo-Hawk’s statistical research helped shape Lekanoff’s MIPA legislation, showing there are systemic racial data barriers when it comes to filing and tracking these reports. It’s an issue Echo-Hawk has been combating in King County.

Only five MIPAs have been issued since July 1. Among them, three individuals have been located, one was found deceased and another is still missing. There are still 126 active missing Indigenous persons in Washington today, and Gosch says any of these names can be announced through the new system — no matter how long they’ve been missing — as long as agencies are willing to do so. A sizable majority of the new missing Indigenous cases, like Williams, are juveniles since the system went into effect.

“If you implement something as delicate as this law that has funding and training behind it, collaboration and consultation, they could have done better,” Lekanoff says. “Luckily, that girl was found.”

Roxanne White from the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Washington leads the 2018 Womxn’s March in Seattle. (Photo by Matthew S. Browning / Real Change News)

Roxanne White has always been a lone roaming warrior whenever she embarks on road trips between Seattle and her home on the Yakama Indian Reservation. It’s a three-hour commute each way, but she doesn’t mind driving that distance for her cause.

The families of missing and murdered Indigenous peoples seek her out, the same way she sets out in search to bring their loved ones back home. The 50-year-old enrolled member of the Nez Perce Tribe spends her days as a full-time volunteer who helps the families of victims, out of her own pocket, in finding their loved ones and coping with the outcome — wherever that journey may lead them.

White has consulted close to 300 families over the course of six years, both in and outside of Washington state. In that same time, White also organized 40 events from marches and rallies to searches in reservations and cities alike. They trust her with their emotional baggage because of the trauma she herself has dealt with throughout her lifetime.

“I was kidnapped. I’ve been sexually assaulted, domestically abused. I was a runaway youth. I experienced all this trauma,” White tells Next City. “I knew I was the [Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women].”

White says these families need to hear her story — a mother of two sons and a broken family, who struggled with alcoholism by the age of 16. She has since been sober for eight years after facing substance abuse issues stemming from her sexual assault history. She wasn’t the only one in her family scarred by gender-based violence, either.

“My aunt was murdered in front of me in 1996, and I also had a cousin go missing in the ‘80s, and she was found murdered,” she says. “So, I realized that not only was I an MMIW survivor, but I’m also a family member. My aunt never got justice, and my cousin didn’t either.”

One of those families was the Williams. She aided the grassroots search to bring her home by creating the first flyer on their behalf. But when White initially heard about her dire situation, she noted the same patterns of pain, trauma and healing faced by the hundreds of families she has worked with.

The rural-urban divide doesn’t disrupt the lived experiences of missing Indigenous peoples either, she says. King County is the 13th largest county in the country, with more than 2.2 million residents. Its agencies usually only have a few more active missing Indigenous person cases than the Yakama Indian Reservation, even though their tribal population is more than 70 times smaller than the county itself.

“My point is that this young lady, she’s many of our missing. All of these girls are me,” White says. “When the families hear this, they feel like recovery is possible. Healing is possible. Change is possible, and to have hope, to not give up.”

Gabriel Pietrorazio is a national award-winning journalist based in Washington, D.C. He closely covers Indigenous affairs, food and agriculture, politics and policy. His reporting has been honored by Native American Journalists Association and North American Agricultural Journalists, among other professional membership organizations. He also earned a master’s degree from the Philip Merrill College of Journalism at the University of Maryland, College Park in 2021.

Matthew S. Browning is a photographer in Seattle.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine