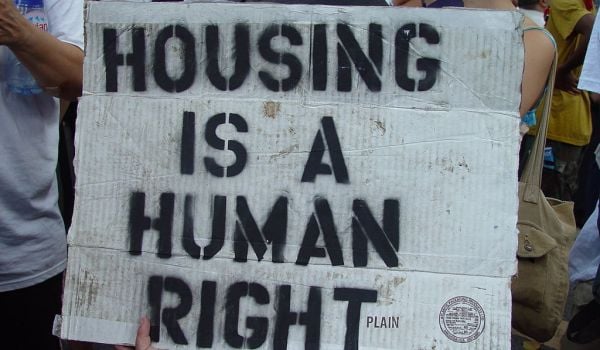

NIMBYism, it seems, never goes out of style. Despite an acute affordable housing crisis in many U.S. cities, getting new homes built for low-income people remains a giant challenge. As has been well documented recently, from Houston to Seattle, that’s due in no small part to NIMBYs. Local residents who, though they may be philosophically in favor of affordable housing, cry out, “Not in my backyard!” when it comes to building in their neighborhood.

There’s no one-size-fits-all solution that will instantly change such residents’ minds. There are, however, a handful of key steps that developers are taking to head off opposition to affordable housing development from the get-go — and diminish it once it’s arisen.

1. Be Proactive

Corianne Scally, a senior research associate at the Urban Institute who has extensively studied NIMBYism, has found that neighborhood opposition typically occurs very early in the development process. As a result, she says affordable housing practitioners need to engage “early and often.”

That’s borne out in practice. “There’s a strategy that usually fails: If we don’t say anything for a while, then maybe we can sneak it in and people won’t have time to organize against it,” says Amy Bayley, vice president of community planning at Mercy Housing California, a nonprofit developer. “That’s a fundamentally flawed idea.”

Bayley follows a fairly strict blueprint for interacting with a given community. First, she and her team identify a handful of local leaders and meet with them to talk about the upcoming project; some eventually wind up on a Mercy-organized advisory council to provide input on the development.

Then — and before the neighborhood learns of the project through official channels — she holds a series of community meetings.

“At a first meeting, we can take the temperature to understand the big issues. We try to communicate with grace and dignity. It’s not about how to organize better than them, but about talking to them,” says Bayley. And Mercy never has just one meeting. “You have to be able to say, ‘Please come back for my next meeting.’ That way, you develop relationships.”

2. Use Respect, Not Stereotypes

At those community meetings and in subsequent interactions, it’s critical to show respect for residents and their anxieties. “We have to try to avoid self-righteousness as much as we can,” says Richard Thal, executive director of the Jamaica Plain Neighborhood Development Corp. in Boston.

That may be tough when the need for low-income housing — whether it’s for the working poor, supportive housing for people with mental illness, units for homeless veterans, or something else — seems so pressing and, well, obvious. And most affordable housing developers agree that elements of racism or classism are often present in neighborhood battles. But there may also be legitimate concerns related to density, traffic or simply a fear of change. Local land use policy is one of a few areas where citizens can genuinely engage; many simply want a sense of ownership over what’s going on in their community.

“For most of us, if we’re honest with ourselves, if someone was building a multifamily development in our neighborhood, we’d be nervous,” say Chris Estes, president of the National Housing Conference. He’d prefer affordable housing advocates stop using the word NIMBY altogether: It’s a stereotype that can be just as pernicious as the one about “those people” who populate affordable housing.

3. Activate Supporters

Rallying those who are in favor of the project might seem obvious, but it’s a frequently overlooked tactic, says Michael Spotts, a senior analyst and project manager with Enterprise Community Partners. He recently helped update the housing element of the comprehensive plan for Arlington County, Virginia, where he lives, and found that the base of support there for affordable housing was a quiet group, compared to a very loud opposition. “One of the things that was critical was a very concerted effort to raise up the voices of the people who really wanted this to happen,” he says.

Thal, in Boston, agrees. In 2010, his organization was engaged in renovating an old nursing home to serve as a medical facility for the homeless, and ran into major opposition in the form of one particularly vocal resident. In response, he says, “we ended up getting over 350 signatures on a petition, and we published an ad in the local paper a week or two later with those signatures, saying that they support this new project.” It absolutely helped, he says.

But don’t forget to also reach out to politicians, the media and members of the faith community. The latter can serve as some of a project’s most powerful supporters.

4. Craft the Message Carefully

The National Housing Conference recently held a communications conference in Minneapolis focused on affordable housing messaging. They acknowledged that the term “affordable housing” often conjures images of crime-ridden public housing complexes — and they also discussed the fact that many Americans struggle with affordability but aren’t eligible for assistance, and therefore don’t necessarily support it for others.

What helps in the affordable housing argument, says Estes, is to talk about the community’s needs, and to point out the cost if, say, firefighters and teachers can’t afford to live there, or if people with disabilities can’t access its services. “It’s not a set of magic words,” he says.

Once the message is in place, it’s important to get it online as soon as possible. Bayley and Mercy Housing California found that out the hard way with a project near Los Angeles. “After our second meeting, someone put comments up on [the social media site] Next Door that [the project] was dangerous and scary. It got 400 signatures almost overnight, with incorrect information,” she explains.

Within a week, she and her team had a website up to counter that false information — something they’ll be doing more frequently in the future. “Anybody thinking about doing this stuff needs to take into consideration the social media side and have that be part of their communications planning,” says Bayley.

5. Leverage What You’ve Got

Personal stories of community members who need affordable housing can be incredibly powerful, say advocates. But again, tailor the story to the audience.

“In Arlington, we heard stories from car dealers whose mechanics live an hour away and have to get up at 4 in the morning to beat the traffic, and then sleep on their lunch break. In a more progressive community that believes in affordable housing, those heartstrings stories can deeply resonate,” says Spotts. In an area with more negative stereotypes about affordable housing, he adds, tales of businesses struggling to find minimum wage workers might be more effective.

Developers should also take advantage of finished projects that show off their good work. “I’ve found that tours of our buildings go really well,” says Sam Moss, executive director of Mission Housing Development Corporation in San Francisco. “If you have 15 minutes or two hours, there’s four different tours we do. It does nothing but good for the entire industry.”

6. Think Bigger, and Encourage Neighbors to Do So, Too

Neighborhood opposition to affordable housing doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It’s enabled by many things, including a regulatory environment that often forces developers to repeatedly consult local government and citizens.

A new movement, aptly dubbed YIMBY (or Yes in My Backyard), is afoot to change that environment. According to Laura Foote Clark, executive director of San Francisco’s YIMBY Action, the group is focusing on removing some of the low-density zoning that limits multifamily housing in many parts of San Francisco, and streamlining the permitting process. “It’s time to rock the boat,” says Clark, who adds that the three-year-old movement is spreading across the U.S. The annual YIMBYTown conference was just held for the second time, in Oakland, California, last week.

Affordable housing developers don’t have to declare YIMBYism to improve the process in their own community though. They can simply advocate for changes at the local level that allow developments to move forward more quickly and without repeated public consultations.

They can also urge neighbors who oppose their projects to think — and feel — bigger, to empathize with those in need rather than considering only their own needs. That isn’t easy to manufacture, but it can be extraordinary when it works.

Moss can testify to that. Mission Housing was working on a project near the Balboa Park BART station in San Francisco that had 100 units and no parking, something the organization had taken into account by locating the development near a transit hub and setting up a ride-sharing component. But neighbors were outraged about the lack of parking spaces.

“Finally I lost it,” remembers Moss. He explained to the assembled group that every parking space represented a unit of affordable housing that wouldn’t get built. “I said, ‘We’re not in the business of housing cars. Would you rather do that?’ And it stuck. People were like, ‘OK.’ It was a magical, mythical moment I wish I had on camera.”

Amanda Abrams is a freelance writer based in Durham, North Carolina. Read more about her at amandaannabrams.com.

_920_614_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)