Renovations recently outpaced new building construction in the U.S. for the first time – great news for those concerned about climate change. The building construction industry is responsible for a hefty 13% of energy-related emissions.

Reusing our existing building stock can help us avoid significant environmentally-costly new emissions, while also providing opportunities to reduce building operating emissions through energy upgrades. It’s estimated that reusing and retrofitting existing buildings can save between 50-75% of the carbon that would be expended by constructing a similar building.

This new trend in building and infrastructure reuse, driven primarily by dramatic increases in the cost of building materials, contrasts significantly with America’s longstanding love affair with chucking out old buildings in favor of new ones. In total, we typically demolish more than a billion square feet of built space in the United States every year, the equivalent of 20% of the built area in New York City. This means that in the next 10 years, we’ll demolish (and rebuild) the equivalent of New York City…twice. In addition to those teardowns, we abandon many buildings. Though estimates are imprecise, it’s believed that, across the U.S., as many as 19 million buildings sit vacant.

Yet our appetite for space is enormous. It’s estimated that we build between four and six billion square feet of space, between residential and commercial development, in the U.S. each year. But the climate impacts of all that building – including emissions from materials manufacturing and new infrastructure – receives far less attention than it should.

It’s true that the lion’s share of energy-related emissions from the building sector (27%) come from the operation of buildings, so the 13% of emissions from construction seem less significant in comparison. While we unequivocally cannot meet our carbon reduction targets absent efficiency upgrades to and electrification of existing buildings, we also cannot build our way to net zero. The carbon impacts of new construction present a significant and underrecognized barrier to meeting our carbon-reduction targets, specifically because of our failure to think about the timing of those emissions.

When assessing the best way to cut emissions in the building sector, we must think not just about how much carbon we reduce – but when those reductions happen. Since greenhouse gasses accumulate in the atmosphere and we have limited time to reduce these emissions to stave off the worst impacts of climate change, immediate carbon reductions have more value than reducing carbon at some later date in the future.

Herein lies the challenge for new buildings. The carbon released into the atmosphere from producing and transporting building materials and from the construction process is immediate.

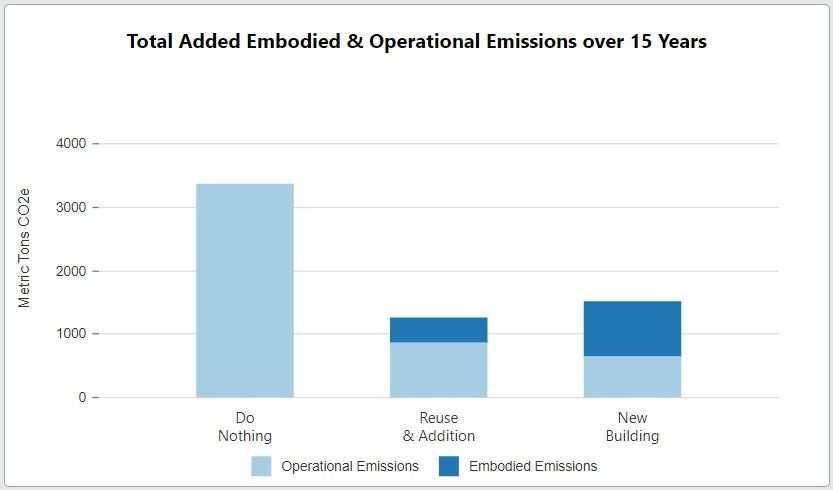

The architectural firm Goody Clancy recently led rehabilitation work at the Alan and Sherry Leventhal Center at Boston University, converting the former Hillel House into a new admissions center. Using the new Carbon Avoided Retrofit Estimator (CARE) Tool developed by Architecture 2030 and colleagues, the architects found significant emissions reductions associated with the renovation of the building compared to demolition and new construction.

Goody Clancy Analysis of Leventhal Project with CARE Tool.

The firm assessed three scenarios over a 15-year period: do nothing, reuse the existing building with key modernizations and efficiency improvements, or demolish the old building and replace it with a new building.

The first scenario – maintaining the status quo – is the clear climate loser, as the building continues to emit carbon through operations at a higher rate than either the rehabilitation or new construction scenarios. But perhaps counterintuitively, reusing the existing building (even if not as energy-efficient as a new build) would emit far less carbon over 15 years than a new, considerably more energy-efficient building. That 15-year assessment period represents roughly the time period in which we have to achieve to meet Paris Agreement targets.

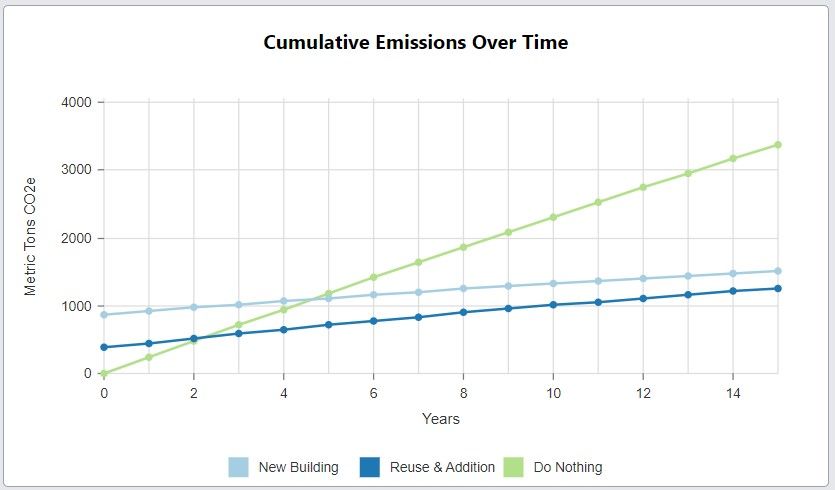

When emissions from the Boston University project are graphed over 15 years, we can clearly see the higher short-term carbon emissions under the new-construction scenario (see the graph below). As climate scientists are quick to remind us, in this near-term period we must do everything we can to bring down emissions.

Goody Clancy Analysis of Leventhal Project with CARE Tool.

The analysis performed with the new CARE Tool is consistent with many other studies conducted over the years, with typical findings that it will take 10-80 years for replacement buildings to achieve a lower carbon impact than the rehabilitation of existing buildings.

The science is solid, and the data are clear: Reusing and retrofitting existing buildings is vital to achieving significant emissions reduction targets. The question is no longer whether to reuse what we can, it’s how to do it.

Many barriers to building rehabilitation remain, not the least of which is the difficulty of financing these critical projects. This is particularly true in communities of color, where systemic barriers to lending remain, and in disinvested rural areas where underlying market conditions make the economics of adaptive reuse difficult and there are relatively few lenders.

We must develop creative financing strategies to make building reuse happen more efficiently and at scale. Allowing new federal Greenhouse Gas Reduction Funds to support building reuse and retrofits, the improvement and expansion of historic tax credits, and making permanent the New Markets Tax Credit program are among the many policy advancements needed to help better leverage our existing built assets in the climate fight. We don’t have a moment to waste.

Patrice Frey is Senior Advisor to Main Street America. Vincent Martinez, Hon AIA, is President and Chief Operating Officer of Architecture 2030.

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)