In Feb. 2017, the city of Madison, Wis., was developing its comprehensive plan. Michael Ford noticed that the plan, which projects 20 years into the future, had no input from young people.

“You have these planning meetings and it’s the same people in the room,” says Ford. “We were looking 20 years into the future, we have young people who are going to inherit that plan while they are in their prime. They should be at the table talking about it.”

So he pitched the office of Mayor Paul Soglin. The way that the meetings were set up right now, he told the mayor’s office, it’s not interesting to young people. But he had a “crazy idea to do something with hip-hop.”

As a student pursuing a master’s degree in architecture at the University of Detroit, Michael Ford observed cross-pollination between hip-hop culture and architecture. For Ford, a Detroit native, hip-hop tracks such as “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five represented observations on the ground about how failures in architecture and design often disproportionally adversely impact low-income black and brown communities.

Ford detailed his observations in his master’s thesis, entitled “Hip-Hop Inspired Architecture and Design.” Since then, Ford has shared his insights in a series of presentations, including a TedX Madison talk titled “Hip-Hop Architecture: the Post Occupancy Report of Modernism,” a multi-media presentation at the national convention for the National Organization of Minority Architects (NOMA) in Chicago, and, most recently, a Super Soul Short film produced by Oprah.com.

In Madison, those observations culminated in what became the first Hip Hop Architecture Camp. Hosted by the Madison Public Library system over a series of four Saturdays, the camp invited young people from underserved areas of Madison to plan and build models of their neighborhoods. Participants also had a chance to work with local hip-hop aficionado Rob Franklin, aka “Rob Dz” at the library’s recording studio. The camp earned the Madison Public Library system a “Top Innovators” Award from the Urban Libraries Council in 2017.

“Madison Public Library provided us with space; the planning department provided the funds. I paid for a lot of the stuff myself as well just hoping it would grow afterward. It was much more successful than even we imagined,” Ford says.

For Ford, the Hip-Hop Architecture Camps have become a way to introduce young people to architecture and design who otherwise would have likely never had exposure to the fields. He has since conducted additional Hip Hop Architecture Camps in Tempe, Ariz.; Chicago, Ill.; Evansville, Ind.; Prince George’s County Md.; Boston, Mass.; Detroit, Mich.; Kansas City and St. Louis, Mo.; The Bronx, N.Y.; Toledo, Ohio; Portland, Ore.; Lake City, S.C.; Austin, Texas; Milwaukee, Wis; and also Toronto and Vancouver, Canada. Ford plans to have the camps become an annual event for each city that has previously hosted them.

Autodesk sponsors the camps, nationally. Ford had been working with the engineering and design software company on the Universal Hip-Hop Museum in the Bronx. “I shared what’s happening with the camps with Autodesk and I think it was a natural fit for them as well,” he says. “The camp allowed people to use their software in ways that they may not originally have intended but it also allowed us to introduce architecture and design [to young people]. So Autodesk provided us with some funding to take this program and make it national.”

Each camp addresses issues that related to a particular community. For instance, in Detroit, the Black Bottom neighborhood had been destroyed years earlier by an expressway. Today, however, the sunken expressway is being backfilled and reconstructed as a surface street. Camp participants addressed possible ways to mitigate the damage.

In Chicago, camp participants addressed gun violence, writing and performing a video titled “Build the Hood Up.”

“So, like hip-hop, every region or city or state is going to have a different sound but also different things that they’re addressing in the music, and I think the camps should be the same way,” Ford explains. “So I listen to the music, listen to the young people in that region and that’s where the program is derived from for the camp. The process of how we generate our architecture is always the same but the exact (product) that we’re generating is unique.”

Along with conducting Hip Hop Architecture Camps for young people, Ford and hip-hop recording artist Lupe Fiasco developed the idea of conducting sessions of cross-disciplinary groups of designers and architects, including NOMA members invited by Ford and rappers from a group called the Society of Spoken Art, invited by Lupe Fiasco (who co-founded the group). That concept evolved into a series of what Ford calls “Hip-Hop Architecture Design Cyphers,” so far conducting two in New York City along with one each in Los Angeles, Atlanta, and Detroit.

“The Cyphers are all about exchanging information but it’s also a challenge,” says Ford. “You better come correct or you’re going to get pushed out of the circle. But it’s (also) very supportive, we really challenge each other, we really push the boundaries of the culture but also of design as well.”

The Cyphers have helped Ford generate ideas and themes for real projects in an inclusive way. “I used this process to generate ideas for the Universal Hip-Hop Museum which ultimately helped them create their capital campaign,” Ford says.

The Cyphers included input from hip-hop rappers and artists, deejays, and graffiti artists as well as urban planners and architects, contributing insights in an equal exchange. One exercise involved highlighting different rhyme schemes with the guidance of the rappers. Those structures were then transformed into architectural patterns and structures with the guidance of the architects and urban designers. The Cyphers have also produced concepts and videos used part of the Hip Hop Architecture Camp curriculum.

“We did the same exact [process] with these professionals and artists, seeing what could happen when you combined hip-hop and architecture together,” says Ford. “The only difference there was that we were no longer studying and thinking about what the artists intended. We had the artists right there in front of us who can explain their processes for getting rhyme schemes into the structure of a song, and we were able to convert those schemes and structures into architecture right there on the spot.”

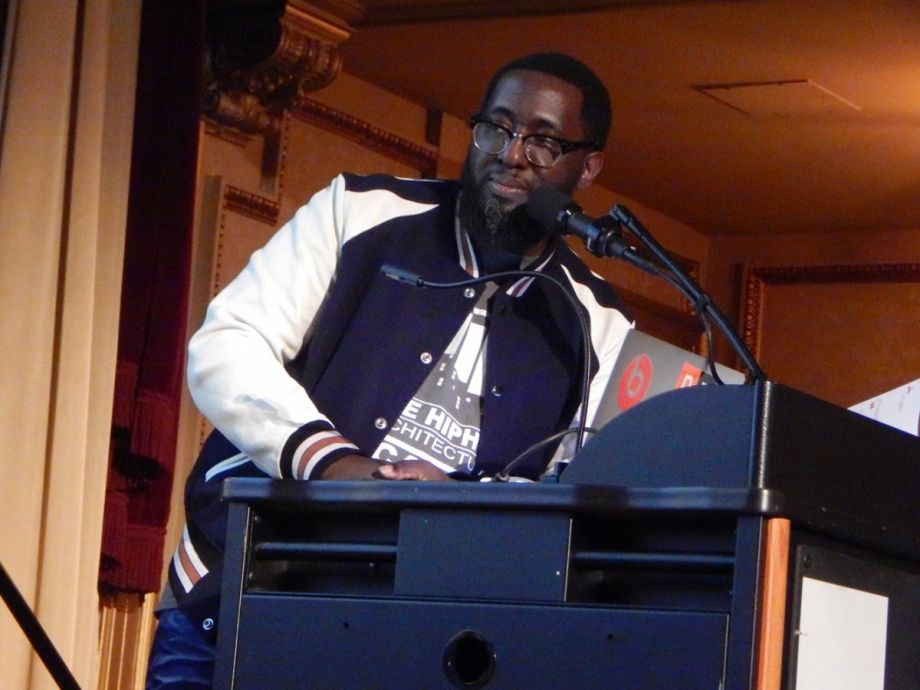

Michael Ford delivering a Hip-Hop Architecture presentation at the 2018 Annual Conference of the National Organization of Minority Architects, Oct. 2018. (Photo by Audrey Henderson)

Meanwhile, the Hip Hop Architecture Camps have also gone global. A coincidence resulted in Ford conducting a special Hip Hop Architecture Camp at the Samburu Girls Foundation in Loosuk, Maralal, in Kenya, during June 2018. He was conducting a workshop to design a teen space at a public library in Madison and needed to use a laser cutter. He remembered that there was one at the School of Human Ecology on the University of Wisconsin campus. While he was using the laser cutter the professor who let him use the tool mentioned that she was organizing a trip to help with the Samburu Girls Foundation, which rescues young girls from early marriage and female genital mutilation. Ford decided he wanted to join the trip to the foundation’s campus, which includes a school for 500 girls but not much else — yet.

“We were able to do a camp and allow the young girls to envision the campus,” says Ford. “We also were able to work with Zero Mass Water and give them access to fresh, clean drinking water.”

Through Ford’s ties to hip-hop artists Lupe Fiasco and Nikki Jean, he was able to connect the foundation with Zero Mass Water, which has a technology that extracts water vapor from the air to create clean drinking water on the spot. Where before the foundation had to have all its water delivered, now they can get some of their water from 40 of the company’s solar-powered water panels.

The trip to Kenya, while not originally part of the itinerary for the Hip Hop Architecture Camp, turned out to be an ideal means of putting its principles into action, according to Ford.

“If you had asked me last year was I going to go to Africa and give 500 girls access to water I would have said no. I don’t see how that’s going to happen. But with the mission we have of using design to solve issues it was a natural fit,” Ford says.

Audrey F. Henderson is a Chicagoland-based freelance writer and researcher specializing in sustainable development in the built environment, culture and arts related to social policy, socially responsible travel, and personal finance. Her work has been featured in Transitions Abroad webzine and Chicago Architect magazine, along with numerous consumer, professional and trade publications worldwide.