Aaron Bolzle, the executive director of Tulsa Remote, a “pay to relocate” recruitment initiative of George Kaiser Family Foundation, grew up in Tulsa but didn’t expect to move back. He attended college in Boston, moved to New York City, secured his dream job in California, then traveled between San Francisco, where he lived, and Los Angeles, where he worked in consulting.

“After about a year of that, I started wondering why I was living in one of the most expensive cities in the world when my job doesn’t require me to do so,” he says. “I wasn’t the first person in San Francisco to wonder why I was still living in San Francisco — the cost of living is getting to the point where it’s not sustainable.”

He ultimately settled back in his hometown and his experience informed Tulsa Remote. Offering a $10,000 grant to remote workers who move to and work from the city, it’s one of a few initiatives around the country attempting to lessen the risk of relocation. In Vermont, there’s the Remote Worker Grant Program to reimburse workers up to $10,000 for relocation expenses. In Topeka, Kansas, Choose Topeka offers matching incentives between employers and an economic development organization to bring workers to the city.

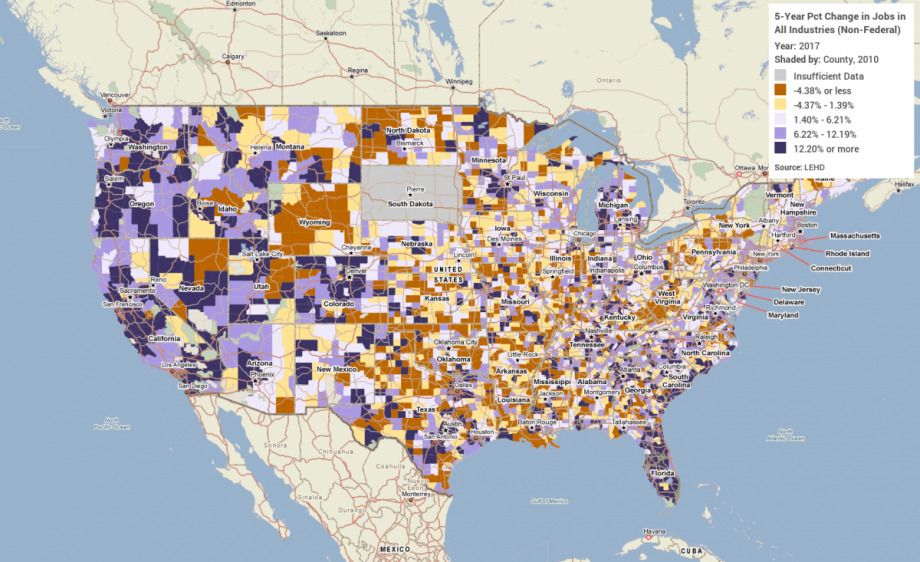

Such initiatives are cropping up as geographic mobility generally, and mobility for work in particular, has declined substantially over the last several decades. A recent report by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR) breaks down the uneven job distribution across the U.S., with large numbers of Americans in economically depressed communities with few opportunities as private-sector jobs increasingly concentrate in a few large cities.

Despite the economy recovering over the decade, low unemployment rates and employers reporting that they cannot find the workers they need — all factors historically associated with an increase in geographic mobility — mobility is stubbornly low. Do “pay to relocate” initiatives offer a meaningful solution or model that could be scaled to a national level? While programs like Tulsa Remote have found success, many U.S. workers will need even more help to take the risk out of relocation.

So why aren’t American workers moving? It’s complicated, according to Chandra Childers, one of the authors of the IWPR report. “There’s no one thing that affects everyone,” she says. The data points to a number of fundamental changes in the costs of and economic returns to moving, like the lack of family supports like childcare and high housing costs.

Relocation costs can be prohibitive, while returns for relocating have declined for many low-wage workers. “In the 50s or 60s, relocating from — for example — Alabama to California would increase your earnings even in the same job,” explains Childers. “The earnings made it worth it for me to relocate. That’s not the case anymore.”

The report proposes a number of policies that reduce barriers to mobility, including housing subsidies and raising the minimum wage. When it comes to the prohibitive cost of relocation, IWPR points to a different report, released in 2015, that studied a federal “labor market intervention” in Germany providing financial support to unemployed job seekers willing to move to a new region.

The majority of Germans who took advantage of the relocation program found higher earnings and more stable jobs, according to report author Steffen Künn. So doesn’t it make sense for governments to invest in relocation assistance? “Yes and no,” says Künn. “Yes, it’s working, everybody who moved into this program has better market outcomes and prospects than those who didn’t do it. No, at the same time, because we have some concerns.”

His first concern is the “deadweight effect”: meaning the program subsidizes workers who have the resources to move without any subsidy. “It’s something we should not underestimate,” Künn adds.

It’s also a valid concern for relocation programs in the U.S., which typically target remote workers seeking to leave high-priced big cities. There’s a higher chance these workers have more resources to relocate than an individual living in public housing, who’s making minimum wage but depends on their affordable housing. To truly attract a diverse workforce, Chiders points out, low-income workers need relocation support alongside guarantees in affordable housing, childcare and a higher minimum wage.

Luring remote workers from larger, more expensive cities was indeed the early goal of Tulsa Remote. Over 10,000 people applied from all 50 states, with 115 people relocating in 2019. This year, Bolzle says, the goal is to bring up to 400 new residents. “The $10,000 is meant to grab people’s attention,” he says, “But also to remove the risk of moving to a new city.”

Bolzle acknowledges the risk of relocation goes beyond moving costs. To that end, Tulsa Remote connects participants to housing resources, community programming and coworking office space. “A lot of programs that have launched have missed the mark by being very transactional,” he says. “We focus on community because that’s why people move.”

He hopes that bringing in newcomers will support low-income families who already live in Tulsa, by providing more diversity in the city’s economy. He also notes that Tulsa Remote is part of a larger initiative by the George Kaiser Family Foundation to address early childhood education, community health, social services and civic enhancement in the city.

The program is entering its second year; time will tell if it affects economic diversity and increased opportunities in the long run. Understanding the long term benefits of relocation subsidies is still to come — Künn notes there aren’t studies analyzing if relocation incentives pay off economically or if incentives mostly benefit people planning to relocate regardless. While Tulsa Remote is privately funded by the George Kaiser Family Foundation, other programs like Vermont’s are supported by public money. “If you’re spending public money, you have to see what really needs it,” Künn says.

Another concern in the U.S. is that while federal relocation programs aren’t unprecedented, one of the most ambitious isn’t considered successful. The Trade Adjustment Assistance Program was formed in 1974 to offer training, job search and relocation allowances to workers adversely affected by foreign trade. But evaluations find the program doesn’t work well, with several studies showing most trade-displaced workers end up relying on Social Security and disability benefits, rather than the resources provided by the program.

It all underscores the necessity of across-the-board supportive services for American workers, including investments that reduce the need for geographic mobility in the first place. But for those cities encouraging people to pick up and move there, “We need to know those communities also have resources,” Childers says. “Workers need to know that they will be able to find a job, affordable housing and the support they need.”

Emily Nonko is a social justice and solutions-oriented reporter based in Brooklyn, New York. She covers a range of topics for Next City, including arts and culture, housing, movement building and transit.

Follow Emily .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)