In 2007, Dorothy Simmons sued to get custody of her two grandchildren after their sibling died. Jordan and Bianca, now 16 and 15 and both with special needs, went to live with Simmons and her father in the family home in Buffalo, NY. Then, in 2015, Dorothy lost her father to lung cancer. The two of them had co-owned the home, and had taken out a reverse mortgage on it.

“They notified me by mail, as being one of the owners, they wanted to know what was my intention,” Simmons says of the mortgage company, Southwest Mortgage. “One of the requirements of him when he got [the mortgage] was that, in the case of a death, it had to be satisfied or they would take the home.”

Simmons had two options: vacate the home and turn it over to the mortgage company or find financial assistance to payoff the reverse mortgage. “I just started crying and thinking ‘What am I going to do?’” she recalls.

Trained as a nurse’s assistant, Simmons hadn’t had steady work in that field for a few years. She had found work performing inspections for a major hotel chain. The amount remaining on the original reverse mortgage approached $50,000, but after an appraisal, Simmons had to come up with just under $15,000 — still, it was a steep price for a senior citizen caring for two special-needs children, one of whom requires homeschooling.

Simmons turned to the same legal organization that had helped her gain custody of her grandchildren, the Western New York Law Center.

“It was really tough,” she says. “It was a tough time for me and the kids because I didn’t know what our future was. I didn’t know where we were going to go. I didn’t know if I could get a loan. My credit wasn’t the best at the time. It just wasn’t.”

Simmons says she lost her hair as a result of the stress.

Through an attorney from the Western New York Law Center, Simmons got help from the New York State Mortgage Assistance Program. The program offers interest-free loans of up to $80,000 for eligible homeowners. It’s structured so that instead of having to make monthly payments, participants agree to repay the value of the loan when the house is sold, refinanced or enters default.

“I didn’t know where this came from. All I could do was just thank God, over and over and over and over,” Simmons says. While she anticipated having to make monthly payments, Simmons says that when she learned that she would be able to keep the home without additional financial sacrifice, she “thought it was a joke.”

The money came, poetically, from millions of dollars in settlement payments to resolve a national lawsuit against financial institutions such as JPMorgan Chase, Citi, and Bank of America for unscrupulous lending practices — such as the targeting of senior citizens with reverse mortgages — that helped propel the mortgage crisis. New York State got $130 million as a result of the settlement payments. In turn, the state Attorney General’s office has used those funds to support a number of initiatives to pilot or scale up programs designed to protect homeowners and renters in the same low- and moderate-income neighborhoods that were hardest hit by the subprime mortgage crash.

Last year, for example, the New York Attorney General’s office allocated $3.5 million to the Community Land Trusts Capacity Building Initiative, a partnership with Enterprise Community Partners. New York City, Albany, and Suffolk and Nassau counties received part of these funds with the goal of creating or expanding community land trusts — specialized nonprofit entities created to ensure the long-term affordability and community control of residential and non-residential land.

“Our one-time funding is meant to demonstrate new models and to show a path forward of what success could look like,” says Enterprise’s Elizabeth Zeldin. The organization will be announcing a new request for 2-year proposals for community land trusts in the spring of 2019, and will be announcing a second round of land-bank funding in the new future.

“Even though the [community land trust model] has been around for a while, it’s never been deployed at scale,” she said. “So, it’s really over the past year that [the initiative] has had the funding to do the work. A lot of what the funding has gone to is start-up operations — making sure that the community land trusts have good quality ground leases; making sure they have the staffing available to do the work.”

Another innovative affordable housing initiative funded with financial crisis settlement dollars is JOE NYC. JOE stands for Joint-Ownership Entity, a member-controlled organization of community-based affordable-housing developers. By combining all or part of each member’s housing portfolio into a single entity, JOE provides an economy of scale that enable savings on borrowing and maintenance costs. It helps to ensure affordable housing can not only survive, and can help make it easier to build new affordable housing units.

But now those settlement dollars are starting to dry up. The Homeowner Protection Program, in particular, is projected to run out of money in March 2019 unless someone else, like the New York State Legislature, steps up to foot the ongoing costs of the program.

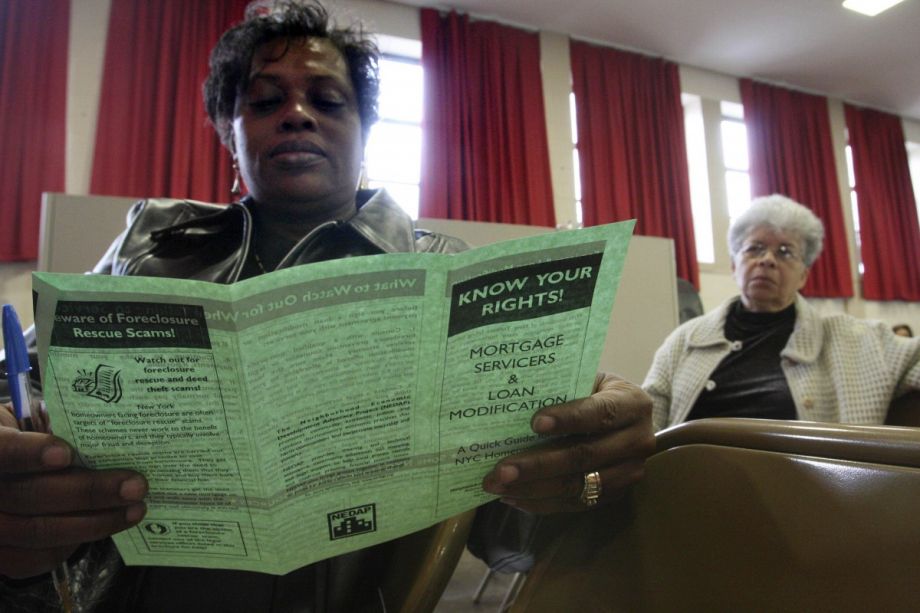

The Homeowner Protection Program provides legal and technical support for homeowners at risk of foreclosure or losing their home, including support for applications to the Mortgage Assistance Program — it funded the Western New York Law Center to help Simmons with her application. Some of the on-the-ground operations under the Homeowner Protection Program have grown immensely. The Center for New York City Neighborhoods, which administers the program locally in New York City, grew from a staff of 10 when it was created in 2008 to more than 80 staff members today, most of whom are working on some aspect of foreclosure prevention.

“Two-thirds of foreclosure prevention services in New York state will go away overnight if the funding isn’t renewed,” warns the Caroline Nagy, who works at the Center for New York City Neighborhoods.

Nagy says her organization has provided more than $68 million in interest-free loans to low- and moderate-income New Yorkers and has helped more than 100,000 homeowners over the Homeowner Protection Program’s 6-year lifespan.

“These are people who a lot of financial consumer and financial protection regulations fall on in a really direct way,” Nagy says, describing how this population has little protection from unscrupulous lending. “And that was something I don’t think that was recognized until the financial crisis happened.”

While Simmons and her grandchildren have managed to keep a roof over the heads, many in New York don’t. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development counted 89,503 homeless people in New York State in 2017. A report from the Coalition for the Homeless found that 63,495 people — roughly a third of whom are children — were sleeping in New York City shelters at the end of 2017. The same report said homelessness in New York City alone has increased more than 80 percent over the past decade.

Along with the Homeowner Protection program, which plucked Simmons and her grandchildren from disaster, funding would also evaporate for a BuildingBlocks, a blight-prevention tool the New York Attorney General’s office funded in 2016.

The Attorney General’s office declined a request for an interview and did not respond to inquiries about the number of people the Mortgage Assistance Program has helped stay in their homes, nor what other programs are facing a financial cliff next year.

“We’ve shifted to trying to get this funding to where, in my opinion, it really belongs, which is having a permanent place in the state budget,” Nagy says.

New York City’s reputation as an economically, culturally diverse place is at stake. A report from the Center for New York City Neighborhoods underscores that many in the city are “shut out of homeownership due to rising costs.” Existing homeowners, it says, are also struggling with taxes, repairs and other expenses in a city where income inequality and the racial wealth gap have become yawning. The Homeowner Protection Program and other initiatives seeded by settlement dollars have kept many of those homeowners in place.

“When we stop funding these services, this is how crises happen again,” Nagy says.

EDITOR’S NOTE: An earlier version of this article incorrectly described the roles of the Homeowner Protection Program and Mortgage Assistance Program in preventing foreclosures or other homeowner loses. We’ve corrected the error.

Zoe Sullivan is a multimedia journalist and visual artist with experience on the U.S. Gulf Coast, Argentina, Brazil, and Kenya. Her radio work has appeared on outlets such as BBC, Marketplace, Radio France International, Free Speech Radio News and DW. Her writing has appeared on outlets such as The Guardian, Al Jazeera America and The Crisis.

Follow Zoe .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)