Cities across the U.S. and Canada have embraced Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), also known as “granny flats,” as a means to quickly address severe housing shortages. Implemented at scale, however, ADUs are a bad urban design solution. They disrupt the neighborhoods they are intended to preserve and can limit, rather than create, social opportunity.

I know because I have lived in one such neighborhood.

Lack of housing availability and rising prices have created a crisis for low- and middle-income Americans. Of the many available statistics, consider just one: At the end of 2022, Moody’s Analytics reported, a median-income household renting an average-priced apartment qualified as rent-burdened.

In this context, ADUs offer many advantages. Defined by the American Planning Association as smaller, independent residential dwelling units located on the same lots as stand-alone single-family homes, ADUs can be relatively quick to construct. They reduce sprawl and lower development costs by adding housing where utilities, roads, schools and services already exist. They address housing affordability both by creating more rental units and by generating income for the homeowners who rent them out. They provide opportunities for multi-generational households by allowing adult children living at home to step up from their childhood bedrooms, aging parents to move in with their grown children (hence “granny flats”), or families of choice to assemble themselves.

The unspoken advantage for communities permitting ADUs as a housing strategy, however, is that they delay the day of reckoning with the land-use policies of the last century. Rather than give up the miles and miles of single-family housing that comprise so much of the nation’s sprawling metropolitan areas, the hidden logic suggests, we can just tuck more people into them. In doing so, we preserve the twin American dreams of home ownership and neighborhood life.

But tucking more people into the backyards and former garages of a single-family neighborhood preserves the dream of homeownership for only a segment of the population, cuts off access to neighborhood life for the rest — and puts everyone in an uncomfortable arrangement.

Living in a neighborhood full of ADUs, as I have done in Santa Cruz, California, is an unsettling experience. This is due to the very nature of their design: ADUs are the secondary unit on a property and are usually located in the back of the lot, often accessed through a gate.

This arrangement creates two parallel neighborhoods. One is a front-facing neighborhood of homes with front yards and front porches where residents might spend time and say hello to passersby, front doors you can knock on if you need the proverbial cup of sugar or are taking the kids trick-or-treating, and opportunities for all the casual neighborly interactions that build community. The other is a secondary neighborhood with no obvious street frontage, limited opportunities for neighborly relationship building, and design-enforced isolation.

Because it is harder to know the backyard tenants, they seem like perpetual strangers. Is that person we see from time to time going through the gate an unmet member of the front-facing family we know, a regular visitor, a vacation rental guest, or a neighborhood resident? Because tenants tend to turn over more frequently than property owners, the question repeats itself before the previous one is fully resolved.

The property owner, the one with the power and greater financial means, most frequently lives the front-facing life in the neighborhood. Their tenant lives the unseen life behind. Financial inequality is expressed spatially and then reinforced as differential access to the social networks of the neighborhood. It is an undemocratic arrangement.

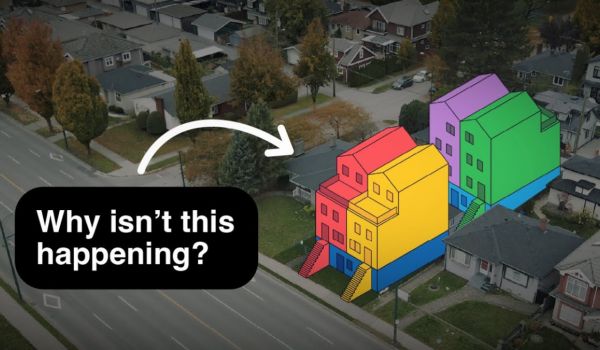

There are better ways to add density while building opportunity and the community life of neighborhoods. One is to embrace the other options within the toolkit of what is sometimes called “gentle” density: duplexes, fourplexes, small apartments and townhomes facing the street. Please, no sideways townhomes strung along a private drive in a once-spacious lot. With these options, two or more residences can fit on an existing lot, equaling or bettering what ADUs provide. Affordability can emerge from the variety of housing types and ages in a transitioning area. These building types put the residents of each unit on an equal footing. Importantly, by being front-facing, they also create equal access to the life of the neighborhood.

This is the approach taken by some pioneering jurisdictions. Minneapolis, for example, ended single-family zoning effective January 2020, allowing the construction of duplexes and triplexes on all residential lots. Oregon passed legislation in 2019 requiring cities with populations above 25,000 to allow construction of duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes on all residential lots. And California’s 2021 Senate Bill 9 allows the construction of duplexes on residential lots and the splitting of sufficiently large lots into two parcels, effectively allowing four housing units to be built in place of one.

So far, these reforms have led to only modest numbers of the newly permitted housing types being built. This slow uptake suggests that the inertia of the single-family neighborhood — due to whatever combination of market preference, the lifecycle of individual properties, or the parcel-by-parcel obstacles of small lots, mature trees, and other site constraints — may not be so easily overcome.

So while allowing gentle density is part of the solution, more direct measures may also be necessary to address America’s housing shortage.

A more direct approach is to build intensively in areas where it makes sense — downtowns, town centers, key transit nodes and along major thoroughfares. This type of density can boost housing stocks in bigger increments and create access to rentals and real estate equity at lower price points, especially where affordable housing requirements apply. It also promotes a lively community built around interactions in common spaces — the street, public gathering places and neighborhood businesses.

Cities need to take action to address housing shortages and declining affordability. Rather than pursue the seemingly easy option of permitting more ADUs, they should use the familiar built forms of denser neighborhoods to create housing and community for more of the population at the same time. That’s good planning and good urban design.

This article is part of Backyard, a newsletter exploring scalable solutions to make housing fairer, more affordable and more environmentally sustainable. Subscribe to our weekly Backyard newsletter.

Travis Beck is a landscape architect and public servant in Santa Cruz, California. He is the author of “Principles of Ecological Landscape Design.”

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)