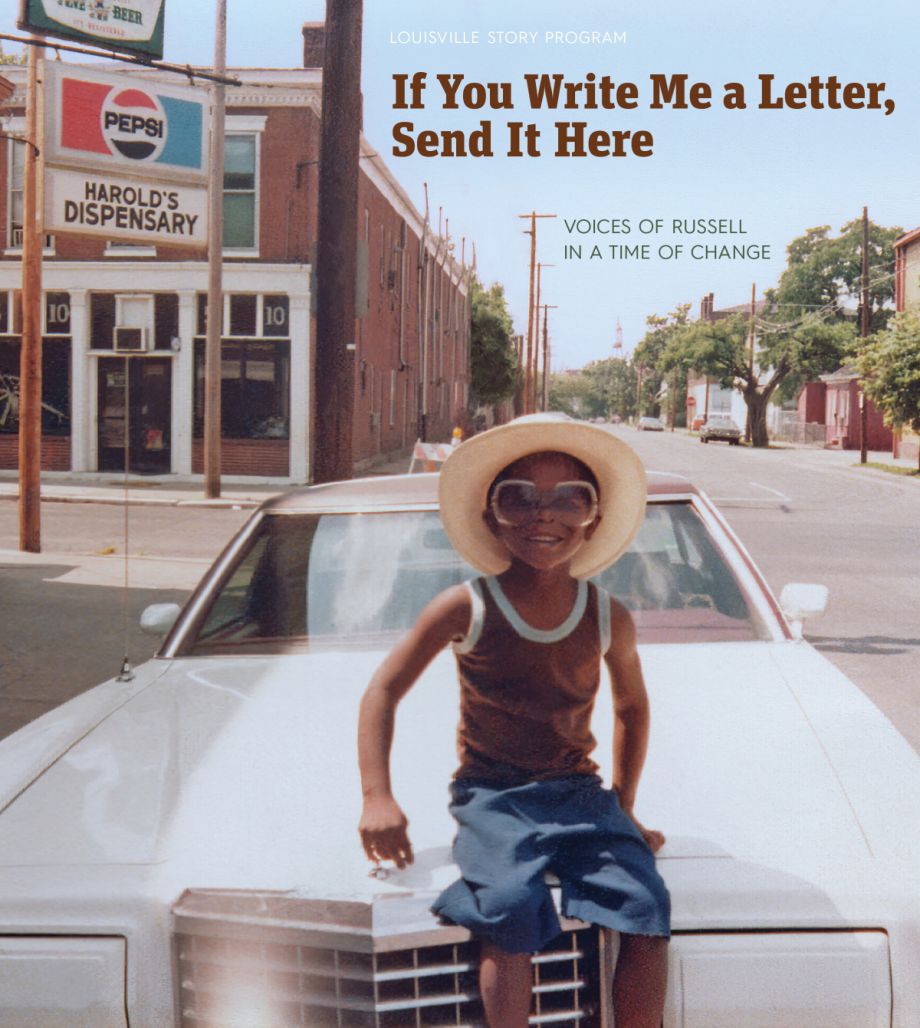

You can judge this book by its cover.

In the foreground, wearing oversized sunglasses and white hat, sits the grandson of Joyce Woods, one of 26 contributors to the book. “If You Write Me a Letter, Send It Here: Voices of Russell in a Time of Change” is titled after the chapter Woods authored. The name speaks to her and her co-authors’ deep roots in the neighborhood of Russell, once called “Louisville’s Harlem”: Born and raised at Russell’s 19th & Walnut Streets, Woods has no intention of leaving. When urban renewal came to take her original home, they offered her relocation elsewhere, but Woods made them build a house for her on the same block.

“If You Write Me a Letter, Send It Here: Voices of Russell in a Time of Change.” (Courtesy of Louisville Story Program)

In the background of the cover photo is the former Saunders’ Five & Ten store, right at 19th & Walnut in the heart of Russell, one of nine neighborhoods that make up Louisville, Kentucky’s historically-Black West End. There was once also a fish market next door. The West End had many thriving commercial corridors like this one before redlining, deindustrialization and urban renewal took hold in Black neighborhoods all across the country.

None of those West End corridors was more vibrant than old Walnut Street, since renamed Muhammad Ali Boulevard. It was there, at the Louisville Central Community Center where Russell gathered April 13 to celebrate the new book, published by the Louisville Story Program, a decade-old nonprofit that has produced ten publications featuring voices from the city’s historically under-resourced communities.

It’s an interesting moment to be from Louisville. As co-author Rev. David Snardon noted at the launch, the mass shooting that took place at a downtown bank last week was just a physical manifestation of broader structural violence that society has long inflicted upon Black Louisvillians in particular.

“This is a place in light of all that’s happened, the death, the destruction, the disappointment that many of us have felt for generations, for decades, for years, and now it’s come home to hit a broader Louisville,” Snardon said.

The work behind the book began back in 2019, with the Louisville Metro Government as the lead funder for the book. The city had recently begun the demolition and redevelopment of Beecher Terrace, a public housing community formerly covering more than 30 acres at the eastern end of Russell, right along Muhammad Ali Boulevard. It abuts the “9th Street Divide,” as it’s known in Louisville, separating Russell from downtown.

With funding from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Louisville Metro Housing Authority had made the decision to replace Beecher Terrace with a mixed-income housing community — following the disputed theory that concentrating poverty in large public housing developments was a problem that needed to be resolved.

The local housing authority offered former Beecher Terrace residents first right of refusal on new units as they were to come online. And it offered temporary relocation to all Beecher Terrace residents in the meantime. According to data provided by the Louisville Metro Housing Authority, so far out of 223 units that have come online in the first three phases of the Beecher Terrace redevelopment, 117 of those units are occupied by former Beecher Terrace public housing residents.

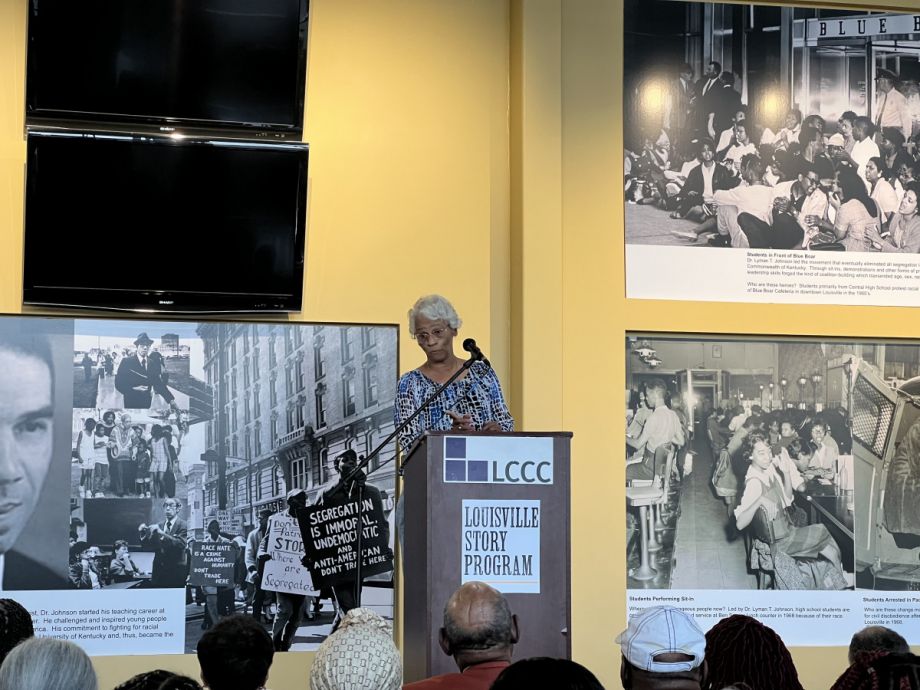

Co-author Joyce Woods speaks at the book launch for “If You Write Me a Letter, Send It Here: Voices of Russell in a Time of Change.” (Photo by Oscar Perry Abello)

But the Beecher Terrace redevelopment has already resulted in the permanent loss of at least one former Beecher Terrace resident from the West End.

Co-author and fashion entrepreneur Ramiriz Reed’s chapter describes the former Beecher Terrace, where he first came to live in 2012, in stark contrast to mainstream reports focusing on Beecher Terrace’s high unemployment rates and high rates of residents lost to racist policing and mass incarceration. Beecher Terrace, Reed described, was “the only place in the city where you could bring your family, your girlfriend, your son, and your daughter, and get you hair cut, your daughter and her girlfriend’s hair done — cut, styled, braided or whatever — and be able to get your pants altered and probably catch someone selling household cleaning supplies.”

Reed’s chapter tells his story of looking for an apartment after he was told to relocate from Beecher Terrace. He encountered landlords discriminating against those holding Section 8 vouchers, including those given to residents as part of the relocation assistance. Some landlords ghosted folks as soon as they heard they previously lived in Beecher Terrace. He moved out of Beecher Terrace and the West End in 2021, finding a new apartment in the Crescent Hill neighborhood on the east side of Louisville.

“The new Beecher Terrace is Beecher Terrace in name only,” Reed writes in his chapter.

Beecher Terrace’s redevelopment is just one component of what has already been more than a billion dollars invested in the West End over the past decade or so, much of it public dollars intended to help begin the process of reversing generations of disinvestment across the nine West End neighborhoods. More investments are coming — particularly along the Broadway corridor, which cuts east-west across the entire West End all the way to Shawnee Park, on the banks of the Ohio River.

But between the market-rate units coming on the market as part of the redeveloped Beecher Terrace and other new developments in the West End — some with public subsidy — there is concern that the West End will continue losing its Black population, as higher property values lead to higher rents.

Rising property values would only benefit an estimated 18% of West End residents, as the rest of the population are renters. And rising rents have already contributed to displacement in the area: According to the U.S. Census, between 2010 and 2020 the Russell neighborhood lost about 2,450 Black residents, while its white population rapidly increased.

There’s no dispute that policymakers have intentions to drive up property values in the West End. Part of the larger redevelopment plans include the West End Tax Increment Financing District, or West End TIF. Created by state legislation in 2021, the controversial measure will take 80% of all new property taxes above a baseline value and place those funds into a dedicated account to subsidize new development projects in the West End TIF area. The legislation also created the West End Opportunity Partnership to control and decide how to spend those dollars.

Local reporters noted last year that the West End TIF is Kentucky’s largest, covering all 12 square miles of the West End, and is unique in the discretion given to allocate the dollars through a quasi-public entity. Usually in Kentucky, TIFs are associated with specific projects — like the TIF district that helped fund the KFC Yum! downtown arena — and require legislator approval up front for a TIF to fund a specific project.

The West End Opportunity Partnership’s board was to include representatives from each of Russell’s nine neighborhoods, but the 21-member board includes 12 members appointed directly by the governor. Some initially appointed board members have since resigned, citing concerns that the partnership may not be taking West End residents’ concerns seriously.

The Historically Black Neighborhoods Assembly, a grassroots advocacy group in Louisville, has been spearheading a campaign to abolish the West End TIF. The group is instead pushing for a new Historically Black Neighborhoods Ordinance that would require any development seeking any public assistance — in the form of public funding, public land or public staff support — to first provide evidence that it will not result in displacement of existing residents or businesses directly or indirectly as a result of rising property values and rents.

Now about 100 days into his first term, Louisville Mayor Craig Greenberg had previously – while working as a developer – helped craft the West End TIF legislation and pushed for its passage. The mayor was on hand in Russell at the book’s launch to make some brief opening remarks.

“As we grieve today for the six victims of gun violence on Monday, as we grieve for victims far too often in our city to gun violence, let’s use that strength to come together,” Mayor Greenberg said. “Let’s ensure that part of that is working with some of the amazing people who wrote stories in this book to use their knowledge of history to ensure our future is better than the past.”

Despite all the challenges facing Russell and Louisville’s West End, the book’s co-authors struck a proud but cautiously optimistic outlook, grounded in all that they believe is still worth fighting to preserve in the neighborhood — be it their homes, businesses old and new, or public spaces whose modest appearances often mask much deeper meaning for those who still live here.

Co-author Rev. Geoffrey Ellis summed up the moment succinctly on Thursday evening.

“Russell is on the move,” Ellis said. “Things are happening in Russell, things are being built in Russell, apartments are being built in Russell, hospitals are being built in Russell, but we don’t have the people coming back building homes in Russell.”

This story has been corrected to reflect that Mayor Greenberg had worked toward the creation of the West End TIF as a developer, not a legislator, and that legislators approve TIFs in KY rather than voters. We regret the errors.

This article is part of The Bottom Line, a series exploring scalable solutions for problems related to affordability, inclusive economic growth and access to capital. Click here to subscribe to our Bottom Line newsletter.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)