Our conversations about gentrification have grown more convoluted in recent years. To those who casually invoke the term, it is still perceived as a straightforward process, visually evident in the disparity more moneyed, typically white newcomers in historically working class, nonwhite neighborhoods. But the role that housing, new residents and incongruous storefronts play in residential displacement has been questioned by researchers, press and policy makers in recent years. The theme in some of this discourse has been that gentrification is either overblown or is a bad word for a natural process.

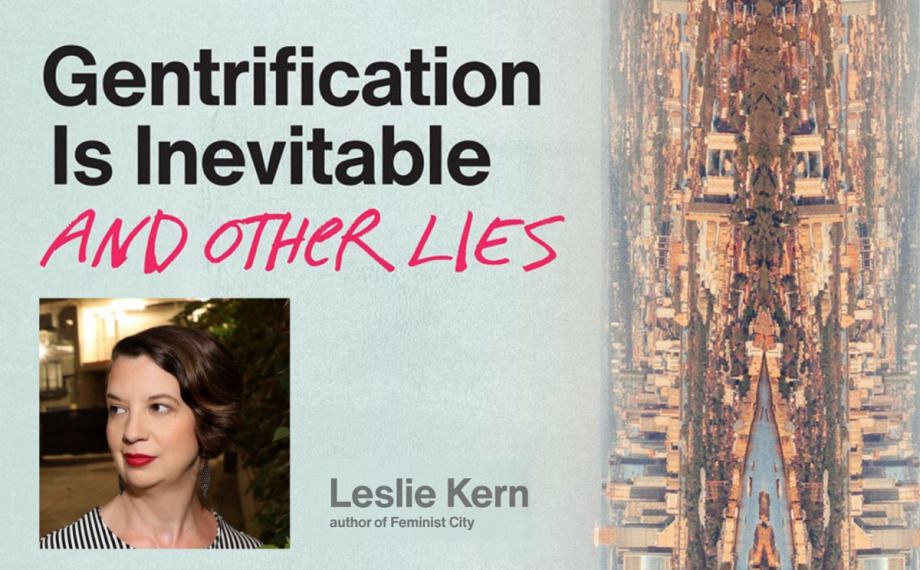

In her new book “Gentrification Is Inevitable And Other Lies,” Canadian urbanist and feminist scholar Leslie Kern turns her eye toward gentrification, focusing on the way that it is framed rhetorically as a benefit to communities, while also challenging the emphasis that some opponents put on the aesthetic markers of gentrification. The book advocates for an intersectional approach to understanding the complex dynamics of contemporary gentrification, making what Kern describes to Next City as “a plea for people to keep in mind this range of power structures that play into gentrification.” In this conversation, we talk through the challenges of navigating gentrification discourse. Our interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Next City: There’s been a new wave of remote workers with high salaries able to move to different cities. How has that changed the nature of gentrification?

Leslie Kern: It’s brought gentrification to the doorstep of smaller cities and communities that weren’t really facing it on any large scale. Where I live in New Brunswick, it’s a place that people drive through. Nobody comes here. But since the pandemic, many people, in part because of this freedom and in part because they are being pushed out by really high prices in cities like Vancouver and Toronto, have come to the East Coast to smaller cities. Not to blame them as individuals, but they probably have a higher kind of income than the average person who lives here.

That movement has triggered a wave of investors buying up buildings in order to renovate them and rent them out to new, higher-paying residents. The pandemic and that remote work possibility and the movement of some people is shifting the frontier of gentrification to places that had not really been grappling with it before.

Your book looks at different cities including London, San Francisco and Toronto. Were there any differences in how gentrification manifested in the cities you studied?

In different cities, tourist gentrification has played a larger role than in others. The issues around Airbnb and transformation of city centers into tourist playgrounds are more heightened in some places, for example Barcelona or New Orleans.

Speaking of New Orleans, the disaster-related gentrification, disaster capitalism, that leads to gentrification – that’s definitely been more of an issue in some places in terms of creating that vacuum, where new forms of development can swoop in often in a very short period of time to totally transform the landscape.

You talk about amenities that cater to newcomers as potential harbingers of gentrification. But low-income and non-white communities also want and need such amenities, like parks or new storefronts. How do communities bring needed investment without catering to forces of gentrification?

It’s such a fine tipping point where new amenities come in, whether they precipitate a wave of new investment or opportunity-seeking for profit. Some of the strongest barriers to that happening are when there is a solid stable supply of social housing in a neighborhood, where there are other kinds of stabilization features, whether that’s rent stabilization, or other things that make it difficult to have rapid turnover of residents happening in the neighborhood. When it comes to these amenities, it’s a question of, did the community have some say in those amenities coming in the first place?

I talked in the book about the Little Village neighborhood in Chicago. For a long time, they had absolutely no green space in the community, but they fought for the creation of a park that’s now there. It’s a very vibrant and well-used community space and the community feels a sense of ownership over it. It’s not meant for outsiders to say, “Oh, look how nice this is” and come in. It’s very much for the use the community wanted it for. In those cases where the community gets a say in what those amenities are going to look like, they’ll use it and they don’t feel like it’s a sign that they’re going to be pushed out.

There are increasingly scenarios where middle- or upper-income communities oppose affordable or market-rate housing, which would likely not displace them, by invoking the language of anti-gentrification. How do we parse the difference between NIMBYs who co-opt anti-gentrification conversations and people who are likely to be displaced?

Sociologist Japonica Brown Saracino writes about this, where gentrifiers come into a neighborhood but then become “preservationist.” You decide at a certain point that’s enough gentrification. We don’t want any more. So even though you were a gentrifier, you now see things like tall condo towers as a threat to some aspect of neighborhood character, or the property values or some combination of those things. It can turn into this weird intersection of NIMBYism with a sheen of anti-gentrification on it. Or they push back against corporate chain stores coming in. And there’s this co-optation to protect what is already a pretty middle-class or upper-class status quo. We always have to ask questions of who’s benefiting, who’s speaking for whom, in terms of those consultation processes.

In the U.S. there’s a lot of disagreement about how to set up the community input process for new development. Some people think we should get rid of community approval because affluent people overtake the process. What do you think about this?

It’s probably similar in Canada. They rely on whoever from the community shows up to talk about whatever the new development proposal is, rather than doing active outreach to make sure that folks in the neighborhood who might be more marginal or vulnerable – whether it’s seniors, single parents or racialized community members – and actually reaching out to them and getting them involved. It’s very much like, “Well, if you showed up, great. If you didn’t, we don’t hear your voice.”

There’s something to be said for thinking through other processes of ensuring we don’t just hear from those who have the time and energy, the social networks, the assumption that they’ll be listened to, as the only voices that end up speaking and being heard.

There are increasingly arguments that the way to deal with gentrification is to build market-rate housing, and that the additional supply will bring down market-rate rents. Have you given thought to this argument?

It’s not in the interest of many groups to actually increase supply because they don’t want to see prices go down. So I think there’s a fundamental contradiction in there somewhere. I’m not sure how that actually shakes out.

The assumption that the only way to create supply is through private developer-led market-rate housing is an assumption that we have to challenge, because I don’t know of examples where that kind of process has led to a decrease in the cost of housing. If I think about Toronto, thousands and thousands of new units of housing in the form of condominiums have been built over the last 20-25 years. But prices have not gone down. It hasn’t increased affordability around the city, so is doing more of that the answer? I’m not sure.

Lawmakers who want to approve new residential development, stores or taxpayer-subsidized stadiums or shopping centers often make the budgetary argument that increased income tax or property tax revenue will benefit the city or state. What are your thoughts on this argument as a rationale for gentrification?

It’s just a different name for trickle-down economics theory, especially when it comes to those mega-projects like stadiums. In most major cities, these are funded through public-private partnerships where the public takes all the risks. If the project goes over cost, or if something goes wrong with it, it’s the taxpayers that pick up the tab. So whether it’s the Olympics or that sports stadium, as far as I’m aware there really aren’t examples where they have led to a real economic boom for the entire community without it ultimately costing taxpayers a lot of money, especially in the short-term.

We always have to ask: Why do we need to spend $800 million on the Olympics to build a new transit corridor that would cost like $30 million? This weird calculus seems to go on in the minds of these boosters.

In New York City, former Mayor Bill de Blasio would say that communities opposed to his administration’s rezonings wanted to preserve their neighborhood in amber. Did you come across these kinds of metaphors in your research, where opposition to gentrification is viewed as regressive?

Yeah, absolutely. The idea – that resistance to change is about nostalgia or fear of change or protectionist, where people put up with things they don’t like, whether it’s crime or crumbling infrastructure, because they don’t like change – does come up as pushback against anti-gentrification claims. In some cases, there might be some validity to that. Sometimes there just is resistance to change for its own sake. That’s not uncommon amongst humans to have that initial reaction. One of the things that sparks that fear or hesitation is that communities don’t feel like they have any control over what those changes are going to be.

If we flip that scenario and ask the community what changes do you want, you’re probably going to get a lot of answers, and probably some contradictory ones. But there’s always something that we want better or changed. So it’s not that there’s a total animosity to change. I think it’s an animosity or a fear of change without any control or input.

This article is part of Backyard, a newsletter exploring scalable solutions to make housing fairer, more affordable and more environmentally sustainable. Subscribe to our weekly Backyard newsletter.

Roshan Abraham is Next City's housing correspondent and a former Equitable Cities fellow. He is based in Queens. Follow him on Twitter at @roshantone.