For Los Angeles renters like us, rents are skyrocketing, homeownership is a pipe dream, and bad luck in the form of a medical emergency, a lost job, or a landlord’s whim can push us right into homelessness.

A year ago, a corporate property owner bought the rent-controlled building where we’ve lived for 20 years. They started trying to push us and other longtime tenants out, in an effort to jack up the rents and rake in fatter profits. Like so many of our Koreatown neighbors before us, we expected to be forced out of our homes, out of our neighborhood, even out of Los Angeles entirely.

But we’re still here. In fact, we’ll soon be cooperative owners of the property.

What made the difference was tenant solidarity — and a pilot partnership between Los Angeles County and local community land trusts, or CLTs.

Community land trusts have roots in the American civil rights movement. They can move housing out of the profit-driven real estate market and into the hands of local communities. A recent report on L.A. County’s $14 million community land trust pilot program, which saved our home and many others, shows that CLTs are a comparatively cost-effective means of affordable housing preservation, overwhelmingly popular with the tenants they support.

Our Koreatown apartment was the first home we could call our own after we came to the U.S. For our first Christmas here, we set up our living room with a tree, a couch and a box TV. It was modest, but to us, it felt like a palace. Koreatown was our neighborhood, and our community.

To the corporate developer who bought our building three years ago, however, that apartment was a commodity to rent or sell for a profit — and they certainly didn’t think of it as “ours.” We were a nuisance in the way of higher rents and bigger profits. They made this clear through harassment and threats. In housing court, their attorneys tried to ask about Guadalupe’s immigration status, a veiled threat and a clear message that we weren’t welcome.

That message has been whispered and shouted at working people of color in American cities for decades. We hear it in redlining, in urban renewal and “slum clearance,” in blockbusting, in neglect and disrepair, in gentrification, in predatory lending and foreclosure. We hear it from corporate landlords and flippers and speculators. They tell us that they, not we, control our futures. They say that their property rights outweigh our human rights, and put their profit before our dignity.

The community land trust offers an alternative model. In it, a community-based nonprofit organization takes possession of land as a steward in perpetuity for community needs — in this instance, for housing.

Taking the land out of the real estate market accomplishes two things: It protects the residents from financial speculation, and ensures that the housing will be controlled by the residents themselves. This gives CLTs an advantage over public housing and nonprofit ownership, both of which can produce and preserve affordable housing, but neither of which are fully accountable to tenants or their communities.

L.A. County’s Pilot CLT Partnership Program provided $14 million for the L.A. Community Land Trust Coalition to acquire, rehabilitate and preserve tax-defaulted and other properties for long-term affordable housing. One of the five member CLTs in the Land Trust Coalition, the Beverly-Vermont CLT, has been in a presence in our community since 2008 and is the steward for four residential properties with a total of 48 homes and 75 tenants.

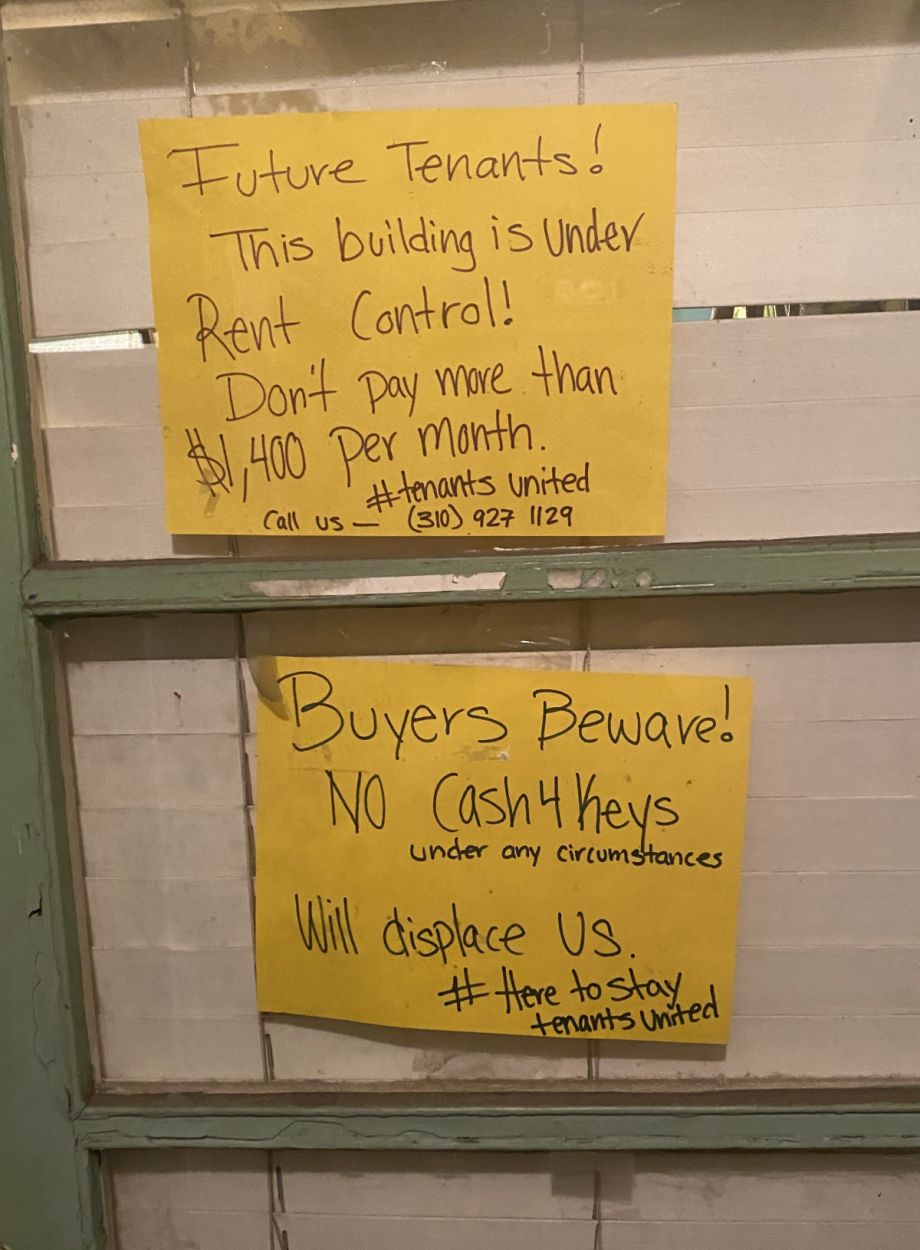

(Photo courtesy of Beverly-Vermont Land Trust)

After we and our fellow tenants fought off multiple eviction attempts, and warned other potential buyers that we would fight any other eviction attempts just as fiercely, we notified the owner of our intent to sue on the grounds of discrimination unless they sold to Beverly-Vermont CLT (where Ixchel is now on the board). Beverly-Vermont, in turn, will create a limited equity co-op that will make us and the other 10 tenants the owners.

In total, the program preserved eight multifamily properties with a total of 43 apartments, housing 110 people. The beneficiaries look like Los Angeles’s working-class and lower-income neighborhoods: Nearly all are Black, Indigenous and people of color.

On average, total development costs for the program averaged $327,523 per unit. This is about half the cost of new construction and 39% less than the cost of acquisition-rehabilitation projects financed through Low-Income Housing Tax Credits. If the program becomes permanent, costs could fall further as local CLTs build capacity and as a larger, more stable funding stream allows for greater financial flexibility.

That last point is key: Cobbling together grants from many places is a slow and expensive process. The passage of Measure ULA in the city of Los Angeles could create that single, permanent funding source.

It’s worth thinking big about what a permanent CLT program can do for tenants in Los Angeles. Playing a bigger role, they could restructure the housing market to make it easier to build and preserve affordable homes. They can empower tenants and their communities. They can even serve as a form of housing reparations for communities that have been damaged by decades of historic redlining, blockbusting and other racially targeted policies — a practical plan to make good on promises of racial justice.

The pilot program has transformed our lives and those of our neighbors in this building. Ixchel is now on the board of the Beverly-Vermont CLT, learning about how this ownership model can work not only for us but for the rest of our community as well. We’re looking forward, with amazement, to the possibility of owning our own home — not for profit, not alone, but to control our own future alongside our neighbors.

We still feel the pain of nearly being driven from our own home. But we are turning that pain into power as we look forward to educating communities like ours about how they, too, can take control of their own futures.

That’s what we did. Because this is our home — and we’re staying.

Guadalupe and Ixchel Hernandez are residents of the Beverly-Vermont Land Trust-owned Señoras for Housing Kenmore.