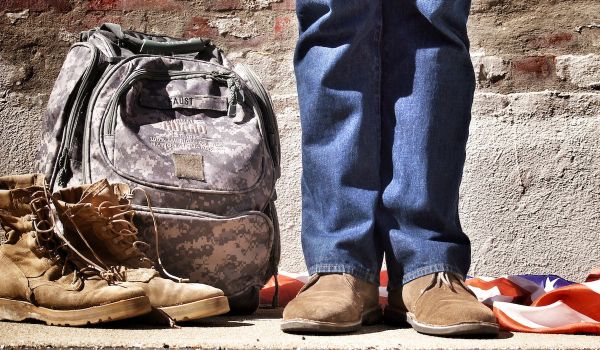

Freddie Tucker joined the army because he needed a job. He ended up making friends and seeing the world.

He finished his service in 1983. Many years later, he faced hardship and stayed in a homeless shelter in Detroit, a harrowing period. After work, he would sit in his car until evening came.

Tucker was determined to find a more comfortable way to live. Thanks to a mental health counselor, he learned about a recently renovated 60-unit apartment building for military veterans like himself.

These days, his life is on the upswing. In August 2022, he was the first veteran to move into the building located in Highland Park, Michigan, a small city within the borders of Detroit. This shift gave the army veteran a reason to smile.

“From where I was till now, it’s like night and day because this is an opportunity that I chose to be in,” Tucker says in an online video. “It’s just everything I need.”

The building, operated by nonprofit Detroit Rescue Mission Ministries, gives veterans like Tucker a much needed permanent housing option while stripping away some long-standing rental barriers, such as bad credit or a record of evictions, depending on their circumstances. These barriers often hinder veterans going through a rough phase from securing an apartment.

On top of that, as more veterans like Tucker move into the complex, the city is a step closer to achieving a key goal in the fight to curb veteran homelessness.

Detroit is one of more than 100 communities in the United States that’s joined “Built for Zero,” a national campaign led by the nonprofit organization Community Solutions that’s supporting efforts to achieve what’s called “functional zero” through a data-driven methodology. Each community has a functional zero threshold, or the average number of people exiting homelessness each month. Reaching functional zero for a population means keeping the number of people experiencing homelessness below that threshold, so the number of people who are experiencing homelessness at any time does not exceed a community’s record of securing housing for at least that many people in a month, per the campaign. Detroit is hoping to reach functional zero for veterans experiencing homelessness.

One study reveals more military veterans are among the homeless population compared to non-veterans. In Michigan, veterans of color are also overrepresented in the overall veteran homeless population, and the state is seeing an uptick in homelessness among older service members. At the Highland Park property, tenants range in age and gender.

A lack of low-cost housing in the downtown area creates challenges for some veterans searching for a place to live, reinforcing the necessity of permanent options with minimal barriers. Once they are housed, veterans gain more stability and security, and get on a path to improve their health and well-being, so they can focus their attention on other parts of their lives, like employment or education.

Already, the collaboration and coordination among nonprofit organizations, government agencies, service providers, and more in Detroit has borne positive results.

“We’ve had a significant reduction in veterans [experiencing homelessness] over the past few years,” says Jennifer Tuzinsky, a social worker and the Health Care for Homeless Veterans coordinated entry specialist within the Detroit VA Medical Center’s homeless programs department.

The department aims to end homelessness among veterans by connecting them to medical and mental healthcare, support services and permanent housing programs. Tuzinsky serves as a liaison for Detroit’s VA homeless programs and the community while also helping oversee the functional zero effort.

The number of veterans experiencing homelessness in Detroit dropped from 348 in 2017 to 119 as of September, representing about a 70% decline, according to an analysis by Community Solutions. That data comes from the Homeless Management Information System (HMIS), which collects client-level data and data on providing housing and services to people at risk of and experiencing homelessness, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). As part of Built for Zero, communities incorporate this data into what’s known as by-name lists.

A by-name list includes information about each person in a community experiencing homelessness, such as health and housing needs, collected in real-time and with their consent. Providers in Detroit working with veterans are trained to input this information into the HMIS. Data consolidation from the HMIS and other local partners combined with outreach to people who may be disconnected from supportive services, has helped communities identify people experiencing homelessness and support them along their path to finding stable housing. Using this approach creates a more comprehensive picture of the homelessness crisis in a community, helping providers connect people to resources more quickly and efficiently, according to a Community Solutions spokesperson.

As those numbers began to drop, Tuzinsky and others noticed that there was a surplus of transitional housing beds, more than was needed. The Highland Park property was converted from transitional housing to permanent housing, providing a low-cost, low-barrier option for veterans while helping fill a critical housing gap.

That conversion was funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Grant and Per Diem (GPD) program, which provides funding for community agencies assisting veterans experiencing homelessness. Additionally, the Rocket Community Fund and the Home Depot Foundation gave donations to pay for the renovation of the units, which have kitchenettes, as well as updated common areas.

In 2018, key stakeholders working to address veteran homelessness in the area began discussions about repurposing the Highland Park property. Eventually, a memorandum of understanding outlined the partnership between Community Solutions and Detroit Rescue Mission Ministries. Design and construction on the building was underway in 2020. Two years later, Tucker moved into his apartment. That collaboration and coordination was crucial in making the permanent housing option a reality and reducing the number of veterans experiencing homelessness in the city.

“I think we built a community where we trust one another and we openly communicate,” Tuzinsky says. “That does not always happen. It takes a lot of work.”

“We have those conversations and we talk about what was working and what was not working,” Tuzinsky adds.

Other boons for tenants at the Highland Park property: veterans may apply to a shorter-term housing assistance program or a longer-term voucher program if they’re struggling financially. The complex accepts both types of assistance to help pay for rent, Tuzinsky says. Right now, rents for studio apartments range from $639 to $670 a month.

“We can leverage different funding sources or supports for the veterans really depending on what their needs are, if it’s financial case management, if it’s connection to other resources for employment,” says Diandra Gourlay, the vice president of social services for Volunteers of America Michigan, a nonprofit organization that provides shelter, food and other services for veterans, affordable housing for older adults, and support services for families in need. At the organization, Gourlay oversees veterans programs.

“Our goal is to get them into housing and get them settled,” Gourlay says. “And work with them to graduate to living independently without financial assistance.”

The Highland Park apartment building is an example of providing a permanent housing option veterans need and want to live in, which involved considerable outreach and feedback from the veteran community. More work needs to be done, Tuzinsky says, to prevent veterans from interacting with the homeless response system in the first place.

A group of community partners and VA staffers are currently working on a recidivism project that will supply deeper insights and develop better supports for veterans who interact with the system multiple times. Making sure veterans have access to information and resources before they become homeless is another route to prevention.

“If a veteran gets behind on rent, the sooner they reach out to us the better chance we have of helping them remain in their housing,” Tuzinsky says. “Sometime[s] by the time they connect with services, it’s too late. We want to connect with them before it reaches that point.”

Right now, there’s momentum, and ongoing collaboration is key to keeping veterans off the streets for good.

“It’s really a whole community effort to just work through and overcome the challenges that we as a system may have created in the past,” Tuzinsky says. “Because we know homelessness is traumatic.”

This article is part of Backyard, a newsletter exploring scalable solutions to make housing fairer, more affordable and more environmentally sustainable. Subscribe to our weekly Backyard newsletter.

Eleanore Catolico is a freelance journalist based in Detroit. Her work has appeared in MindSite News, YES! Magazine, the Detroit Metro Times, the Detroit Free Press, BridgeDetroit, Planet Detroit, Chalkbeat, EdSurge, Eater, WDET, the Chicago Reader, South Side Weekly, and other local and national publications. She was a 2021 Maynard Institute for Journalism Education Fellow.