Credit: SDOT Photos (CC BY-NC 2.0)

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberEDITOR’S NOTE: The following is an excerpt from “Better Buses, Better Cities: How to Plan, Run, and Win the Fight for Effective Transit,” by Steven Higashide, published by Island Press. In it, Higashide presents real-world stories of reform to urban bus systems, shows how to marshal the public in support of better buses, and how new technologies can keep buses on time and make complex transit systems understandable. In this excerpt, Higashide explains how reforming fare-payment strategies can create greater equity in cities.

Bus service shapes the geography of accessibility, and this means how we plan bus service is deeply intertwined with social equity, whether we admit it or not. Transit agencies are required by federal law to analyze whether fare and service changes disproportionately harm low-income riders and riders of color, but this is often performed as a check-the-box exercise. Planning in ways that intentionally advance social equity requires a deeper commitment from transit leaders.

Because bus riders in the United States are more likely to be low income and nonwhite, some argue that advocating for better buses is, by definition, advocating for more equitable transit. But this syllogism, never wholly true, is even less so if we fail to consider questions about the affordability of transit and who feels welcome on transit.

For example, an increased police presence on buses can make some riders feel safer while discomfiting and endangering others. New fare systems can make transit more intuitive and convenient for many riders while being rolled out in ways that worsen transit access for others.

Buses provide spatial access but are also public spaces themselves. How transit agencies seek to ensure safety for bus riders, how they charge for access, and who the service feels intuitive for affects which riders feel welcome on the bus and which are excluded.

Before we go further, a note on the word equity: When I use it, I mean policies that reduce the burdens and mitigate the structural pains put on marginalized communities. I’m talking about transit policies that particularly improve access for, and reduce harm to, racial and ethnic minorities, non–English speakers, women, people with disabilities, and low-income people, whose needs are not centered in public policy. Equity is often used in other ways in the transportation policy world. Legislators often talk about “regional equity,” or whether they perceive that their jurisdiction gets the service it deserves based on how much tax it pays. But the way I use the term is increasingly common usage in urban policy.

More than once I’ve had to go to a convenience store to buy something in order to have exact change for bus fare. One morning in Charlotte I came out of the store just as the bus pulled out—a galling experience in a world where you can summon a taxi or unlock a bike using your smartphone.

Cash is a hassle for both bus operators and riders. Paying in cash tends to take longer than flashing a pass or tapping a card, delaying everyone. Accepting cash requires more complicated farebox equipment, especially if the fareboxes have to give change. On the (now relatively few) buses where operators themselves carry change, theft and robbery are a risk.

Transit operators have been trying to stop riders from using cash almost since the first omnibus plied its trade; in the United States, the transit token, the first fare payment technology, dates to 1831. Today’s transit agencies are upgrading fare collection systems to include smartphone ticketing apps, smartcards with accounts that can be checked and reloaded online, and “open payment” systems that will let riders use contactless bank cards or pay by tapping their phone.

All of these offer more convenience for both agencies and riders. But discussions about fare system technology often sidestep what would be more fruitful discussions about fare policy. New fare payment systems offer big opportunities to make the bus more efficient and equitable.

Transit fares often make arbitrary distinctions between riders, because of technological restrictions or historical inertia. One arbitrary policy that should disappear entirely from bus systems is charging riders to transfer between buses. Consider a grid of frequent bus lines, with a set of routes going north-south intersecting a set of routes traveling east-west. Why should a bus rider who has to go 2 miles in a diagonal line be charged more than someone who has to go 2 miles in a straight line?

And yet some agencies (such as Philadelphia’s SEPTA) maintain transfer fees, even though even a 1990s-era magnetic stripe card is sophisticated enough to encode a free transfer. This is an anachronistic kind of extortion, as if Amazon charged you a “restocking fee” for canceling your order of an online streaming video.

Another inequitable disparity in transit is that lower-income riders often end up paying more than wealthy ones because they can only afford to pay by the ride. Most transit agencies have some type of unlimited pass. An agency where a single-ride bus fare costs $2 might sell a seven-day pass for $20, meaning anyone who takes more than ten rides a week saves money by buying the pass. But the poorest riders may have trouble saving for a $20 pass and end up paying more in single fares.

Transit smartcard technology gives agencies the power to end this unfairness through “fare capping.” A system with fare capping can track how many times the holder uses transit in a week and automatically “cap” the fare at the cost of the weekly pass. Once a person has spent $20 in a week on transit, any additional rides are free. (The same principle can be applied to monthly passes.)

When transit agencies don’t implement new fare collection systems with an eye to equity, they can actually make things worse for many bus riders. In Chicago, the regional Ventra farecard launched with the ability to be used as a prepaid debit card, touted as a way for unbanked people to get into the banking system. But using the debit feature subjected people to predatory fees, such as a $2 charge for calling customer service and a $10/hour fee for “account research” if users disputed a charge. (The debit feature was ultimately discontinued.)

SEPTA’s new farecard, the SEPTA Key, began its rollout in 2016. This new fare system was the perfect time for the agency to eliminate its transfer fee. But SEPTA has not, and it has even gotten rid of the ability to buy paper transfers. This means that bus riders who pay cash now have to pay a full second fare if they transfer to another bus.

One of the best ways to make transit intuitive is to get people transit passes through their school, job, or apartment building. That takes a lot of the guesswork out of transit, and it makes transit seem normal and natural. In Seattle, as many as 60 percent of transit users use monthly passes from employers, partly because of supportive state policy that requires big employers to incentivize nondriving commutes.

In the Bay Area, many residential complexes provide free or discounted transit passes to tenants, thanks to local laws that allow denser zoning for buildings that incentivize alternatives to driving (the advocacy group TransForm deserves a lot of credit for lobbying for these changes).

And across the country, hundreds of colleges and universities include transit passes in the cost of students’ tuition, boosting transit ridership and helping university campuses avoid building expensive parking lots.

Transit advocates are increasingly calling on cities and transit agencies to extend this same convenience to poor and young people.

A bus stop in downtown Seattle features both Rapid Ride wayfinding as well as an ORCA scanner. (Credit: SDOT Photos / CC BY-NC 2.0)

Transit research generally shows that raising fares helps transit agencies’ bottom line; higher fares drive some riders away (for every 10 percent increase in transit fares, expect a ridership drop of 2 to 5 percent), but not that many, so fare increases are revenue positive for agencies.

But as Baruch University’s Alex Perotta has found, transit fares can be an enormous hardship for poor riders. Perotta talked with low-income New Yorkers to complete her dissertation. Many told her that they skimped on groceries, paid rent late, or delayed adding minutes to their cell phones. Others would try to evade the fare when possible. When transit agencies don’t implement new fare collection systems with an eye to equity, they can actually make things worse for many bus riders.

“Fair fares” programs that offer reduced fares for low-income people help bridge the gulf in places such as Seattle and New York, where transit is used by many middle-and high-earning riders who can absorb price increases.

Seattle’s ORCA Lift program offers half-priced fares for riders with household income that is less than twice the federal poverty line. King County officials got widespread enrollment by relying on a network of health clinics, community centers, and nonprofits that had helped sign up residents for health insurance under the Affordable Care Act.

In New York City, the membership organization Riders Alliance joined forces with the poverty think tank Community Service Society and others to win a low-income fare program that began in 2019, although only a small number of people were initially able to take advantage of it because of an underwhelming rollout by city government.

TriMet introduced a low-income fare program in 2018. Not surprisingly, the advocates at OPAL were in the mix. According to OPAL’s Lopez, the fare program was their top priority as voted on by their members. But that wasn’t the only pass program the group was working on. Since 2009, students in Portland Public Schools have received free transit passes during the school year. But these were not extended to students in two other school districts within the city of Portland’s borders, Parkrose and David Douglas.

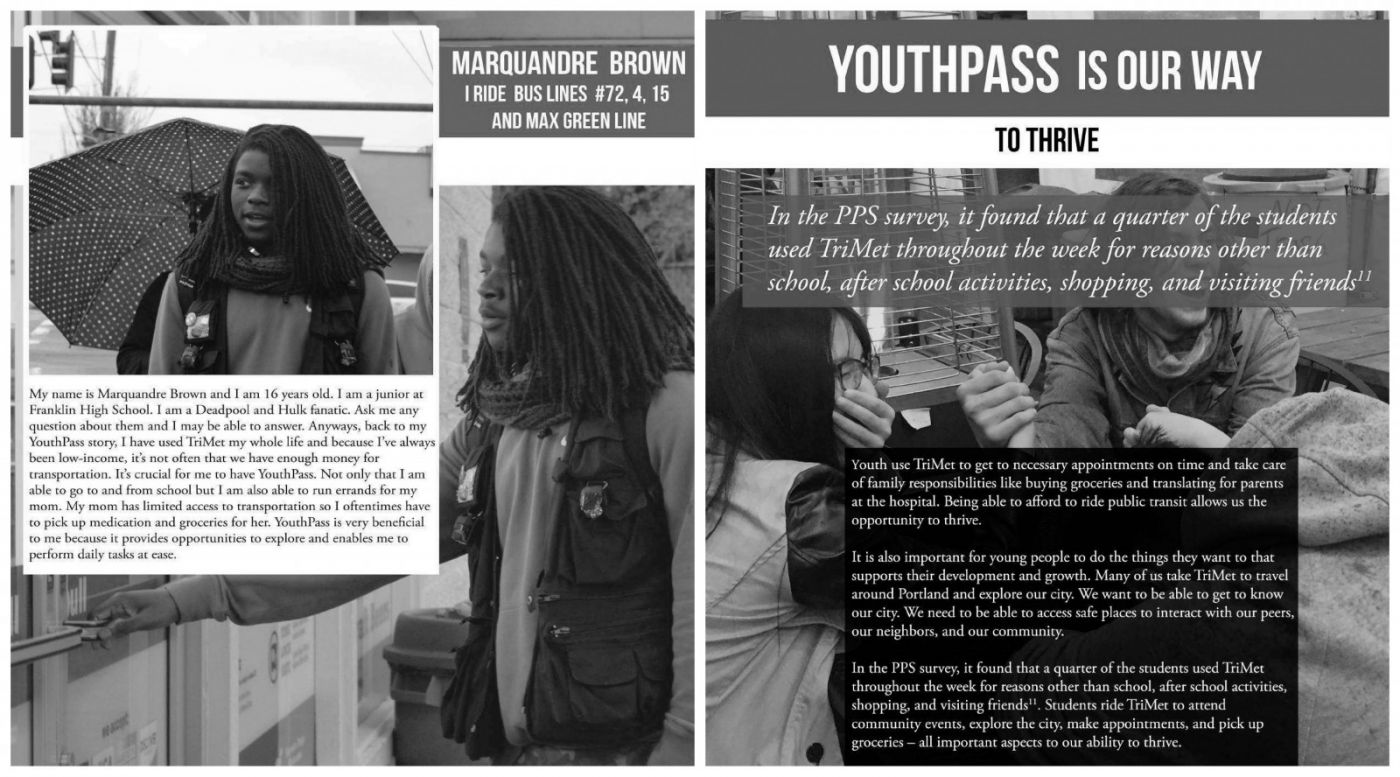

OPAL’s youth pass campaign was run by student members of an OPAL program called the Youth Environmental Justice Alliance. Their members talked to their fellow students at three schools, publishing a “YouthPass to the Future” report that used survey research to call for change. At David Douglas High School, where more than 75 percent of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, OPAL found that half of students used TriMet to get to school. Another four in ten students said that they had missed class because they had missed the school bus; a youth transit pass could allow them to take the public bus as an alternative.

Youth organizers complemented this hard data with earnest stories, profiling students who stayed at school until 9 p.m. so their family could pick them up from activities, walked home for lack of bus fare, and used TriMet to run errands for their parents. According to Fleek, the report was enormously influential, winning an expansion of YouthPass with funding from TriMet, the school districts, and the city of Portland that has lasted for 2 years.

“There’s a two-pronged approach to all the campaigns that we run, and it’s basically the ‘head game’ and the ‘heart game,’” Fleek said. “There are some decisionmakers who will not listen to you unless you’ve got hard data, and there are some who will only listen to you if you’ve got a sob story. But we have to have both.”

Youth transit passes help young people live fuller lives. They may also help seed a new generation of transit riders. Researchers Michael Smart and Nicholas Klein have found that there is an exposure effect when it comes to the bus; riding transit at any age makes people more likely to ride it later.

Fare evasion — when someone gets on the bus and doesn’t pay — is a routine enough occurrence that buses typically have a fare evasion key. This button gets pressed by the operator when someone boards without a fare, so that the transit agency can accurately count ridership figures and identify places where many riders skip the fare.

Of course, transit agencies want to maximize their revenue. But they should resist the urge to get caught up in moralistic dudgeon. A 2017 Portland television spot warned that “thousands of bus riders don’t pay, and most get away with it.” Charles Moerdler, a board member at New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority until 2019, has called riders who don’t pay “thieves” and “lawbreakers.” (Moerdler is perhaps the last person who should make this argument, as he has been repeatedly caught by the media breaking parking laws with his MTA-issued placard.)

A team of researchers found that in the District of Columbia, the three census block groups with the highest rates of fare evasion did not have a single machine or retail store where someone could buy or reload money on the SmarTrip fare card.

Photo by Mike Maguire / CC BY 2.0

On closer inspection, bus fare evasion often turns out to be a crime of poverty or a sign of the system’s inconvenience.

Researchers who have studied the issue have found that a small number of people are hardcore fare evaders who almost never pay (a small group is responsible for a lot of farebeating, in other words). But a much larger number of people fall into the category of “‘not my fault’ evaders,” who have been stymied by something in the transit system itself. This category includes people who jump on an arriving train because the line at the ticket machine is too long or someone who can’t figure out how to use the ticket machine in the first place. These people might literally be at fault, but they wouldn’t have skipped the fare if paying it was easy.

And buses, in particular, can be a pain to pay for. The consequences of missing an infrequent bus are high, meaning that someone who cannot easily pay the fare is more likely to try to push on. Buses often require people paying in cash to use exact change; do you routinely carry $2.75 in quarters?

And unlike train stations, most bus stops lack machines where you can buy a pass. Ideally, transit agencies have partnerships with pharmacies, groceries, and other stores to make transit fare widely available for purchase. But often, these retail networks are sparse and poorly advertised. This raises the specter of people being thrown into the criminal justice system because they didn’t realize they were down to the last 75 cents on their farecard, because they couldn’t break a $20 bill, or because they didn’t want to go a mile out of their way to find a store selling a transit pass.

The research that exists on the demographics of fare evaders suggests that evasion is often the result of economic desperation. A team of researchers from Virginia Tech and NYU found that in the District of Columbia, every area with a high rate of bus fare evasion also had a high rate of poverty. They also found that the three census block groups with the highest rates of fare evasion did not have a single machine or retail store where someone could buy or reload money on the SmarTrip fare card.

As a result, many cities are decriminalizing or otherwise changing fare evasion policy. The Washington, D.C. City Council made fare evasion a civil offense in 2019, eliminating the possibility of jail time for an offense. California has decriminalized fare evasion by minors.

In Portland, OPAL and its allies won legislative and policy changes that replaced the penalty for fare evasion, which had been a $175 fine that required a court appearance, with three less punitive options: a $75 fine for a first offense, community service, or, for poor riders, signing up for TriMet’s low-income fare program.

In Portland, Oregon, the Youth Environmental Justice Alliance’s “YouthPass to the Future” combined survey data with testimonials from individual students about how youth transit passes helped them succeed in school, work, and volunteering. (Images courtesy OPAL)

An equitable approach to fare enforcement becomes even more important as transit agencies implement all-door boarding. Letting riders board the bus at all doors is one of the most important ways to speed up the bus, but because it usually involves a proof-of-payment fare system, it adds roving fare inspectors to the system. It is critical that these personnel conduct inspections in an unbiased way and especially that fare enforcement not be conducted by armed police.

In fact, a judge in Cleveland ruled that allowing police to conduct random fare inspections on the city’s Health Line bus rapid transit violates the constitutional prohibition against unreasonable search and seizure. Unfortunately, the response from the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority was not to use civilian staff but to abandon the idea of off-board fare collection entirely. Cleveland’s Health Line has slowed down and lost riders — an inequitable result for sure.

It is an unfair reality that transit agencies bear the burden of upstream societal failure. Underfunded shelters and overheated housing markets mean that transit agencies are asked to address homelessness. Racist criminal justice systems complicate efforts to reduce fare evasion and keep riders safe. These can feel distant from the transit professional’s expertise of planning better bus routes and managing headways, yet they affect riders’ experience all the same.

Transit advocacy groups need to work with, understand the perspectives of, and listen to the voices of marginalized communities. There are many transit best practices that American agencies should import from other places, from all-door boarding to smarter fare payment systems. But advocates need to recognize how these can collide with some of America’s worst practices, such as violent policing and a patchy welfare system.

By itself, better bus service cannot fully remedy the many structural harms imposed on marginalized groups. But agencies can intentionally plan their service in ways that aim to further equitable access to our cities. All bus riders deserve a transit experience that is safe, welcoming, and intuitive. That may never be completely possible in an oppressive and flawed world. But planners can work for transit that improves access and strive to avoid inflicting greater harm.

Adapted from “Better Buses, Better Cities: How to Plan, Run, and Win the Fight for Effective Transit,” by Steven Higashide. Copyright © 2019 Steven Higashide. Reproduced by permission of Island Press, Washington, D.C.

Steven Higashide is one of America’s leading experts on public transportation and the people who use it. As director of research for the national foundation TransitCenter, Higashide has authored groundbreaking reports that have redefined how decision-makers and journalists understand transit. He has taken the bus in 28 cities around the US and the world.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine