If you’re a driver, you notice highways. It’s the one road you aren’t allowed to cross. For people outside of cars, we notice them too, of course. But for us, especially those of us with disabilities, there are a lot of roads that can feel just as impossible.

Maybe there’s no stoplight, no stop sign, no crosswalk or curb ramps. Maybe there is a light but there’s no audible signal or the countdown isn’t long enough, especially if we have to dodge cars making right turns. Maybe we know cars go too fast and regularly blow through lights, and we’ve been hit or almost hit, or know someone who has. Crossing these high-speed, multi-lane roads, even though they aren’t technically highways, can mean detouring half an hour out of the way, or taking risks that will get us blamed for being “reckless” pedestrians.

I hate the term “vulnerable road users” because of its paternalism and the agency it takes away from those of us outside of vehicles, but the reality is we are less safe than the people in vehicles. Nationally, we are facing a pedestrian safety crisis, and as Smart Growth America’s latest installment of its Dangerous by Design report points out, it’s non-interstate arterial highways where most of these fatal and serious crashes occur.

As the director of the Disability Mobility initiative at Disability Rights Washington, I spend a lot of time talking to other disabled non-drivers – people who, like me, don’t have the option to drive. Unless we can get a ride or get door-to-door paratransit service, we navigate our communities walking or rolling. And in so many of these conversations, I hear about the challenges our existing car-centric infrastructure – infrastructure that too often prioritizes speed over access, creates for non-drivers.

Chris, a low-vision mom who lives in Clark County, just across the river from Portland, Oregon, showed me the walk to her nearest bus stop. It’s along a busy arterial with no sidewalks, 40-mile per hour traffic, and no audible pedestrian signals. “At quieter intersections you don’t feel as unsafe as at busier intersections — crossing a two-lane road versus if you are trying to cross four or five lanes,” she says.

While Chris is willing to take the risk and navigate to this bus stop, many other disabled people decide that it’s just not worth it.

“I would use the fixed route, but I can’t,” Frank, from Benton City in Eastern Washington, tells me. “I can’t walk very far. And also I’m very slow across the street. And I’m very, very, I feel very vulnerable. Crossing the street real slow. The cars are going so fast, if people seem to be distracted, that’s my biggest barrier.”

So Frank relies on paratransit instead, which requires pre-scheduling rides and pickups.

While it’s exciting to see renewed interest in pushing back against highway expansion, as well as new organizing efforts (and even federally-funded programs) to repair the past harms created by dividing communities with limited-access highways, we must recognize that high-speed, multi-lane arterials aren’t the solution either.

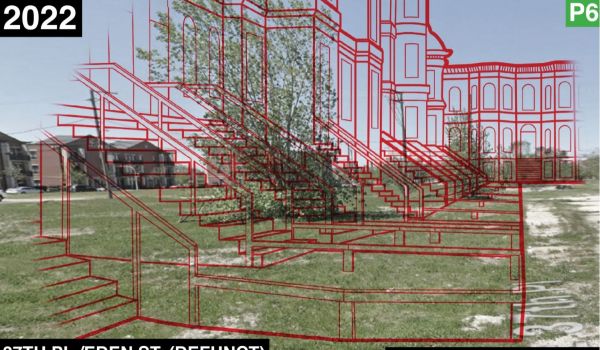

Seattle, where I live now, which has a reputation of being a progressive, green city. In the 1980s, two highways that cut through historically redlined Southeast Seattle were decommissioned as state highways and returned to city control. However, these remain two of the three most dangerous and crash-prone streets in the city (the other being Aurora, which is still a state highway).

The legacy of limiting crossings, and timing lights to prioritize high speeds of cars, persists. This is despite the 25 mph speed limits on both of these now city-controlled streets. There’s a stop light where I cross to the nearest bus stop from my house, but drivers will regularly run through it, as it’s a pedestrian-only crossing; because of the high-traffic noise, terrible sidewalk conditions, and little pedestrian-scale business facades, there are very few pedestrians along this route.

All road widening not only induces more people to drive more often and further, but it also makes life for people outside of vehicles more difficult. For people with the choice to drive, this means more people will choose to drive because being a pedestrian is more awful. And for those of us who can’t drive, it means taking more risks to go to the same places, or forgoing those trips all together.

It’s not enough to tear down highways and replace them with multi-lane, high speed boulevards. While these boulevards may technically accommodate people walking, rolling or riding, they are only comfortable spaces for drivers. If we want to address barriers to access, and the public health and climate impacts of car-dependence, we must make it easier for non-drivers to get around our communities. And dangerous, stressful routes along or across arterial roads are that barrier.

Seattle has another feature I haven’t seen in any other U.S. city: de facto one-way streets in most neighborhoods. Because parking is allowed on both sides of the road, there’s only room for one moving vehicle at a time, so when two vehicles are approaching each other, one has to yield, pulling into a parking spot or backing up to the nearest intersection. This means that on neighborhood streets, drivers have no choice but to travel slowly, resulting in much safer and more comfortable streets for everyone.

What if slow speed streets were the default for our cities? Yes, it would take longer to travel far distances by car in a city, but that may be one of the more equitable ways we can incentivize people to choose other modes, especially if roads designed for slower car speeds were paired with investments in faster bus-only lanes.

In doing so, and investing in higher speed bus or rail connectivity, we will begin to see more people who can choose to, choose not to drive.

For our roads to be safer for people outside of vehicles, for those of us who can’t drive to have more reliable and frequent transit access, more pedestrian-scale storefronts instead of acres and acres of creepy and hostile parking lots, more roads that are slow and quiet enough that we can carry on a conversation with our kid while we’re waiting at the bus stop – we have to reach a critical mass.

That means fighting more than just highways. It means fighting for every street to be somewhere you want to walk or roll along.

Anna Zivarts is a low-vision mom and nondriver who was born with the neurological condition nystagmus. Since launching the Disability Mobility Initiative (DMI) at Disability Rights Washington, Anna has worked to bring the voices of nondrivers to the planning and policy-making tables. Through DMI, Anna has built a nondriver storymap, compiled the expertise in these stories into a groundbreaking research paper and launched the #WeekWithoutDriving challenge for elected leaders to understand what it’s like to get around without driving themselves. Anna represents disabled nondrivers on the Washington State Active Transportation Council, Autonomous Vehicle Work Group and Transit Demand Management Executive Board and serves on the board of the League of American Cyclists and the National Safety Council’s Mobility Safety Advisory Group. Anna received both her masters and undergraduate degrees from Stanford University.